Twayne and Scarecrow:

An Editor’s Memoir

Once upon a time—say 1983—there was almost no serious literature about young adult literature—except, of course, the basic standard work, Literature for Today’s Young Adults by Ken Donelson and Alleen Pace Nilsen. I had been trying since 1978 to create a body of critical work in my “YA Perplex” column for the Wilson Library Bulletin, and other critics like Michael Cart, Betsy Hearne, and Zena Sutherland had done some thoughtful reviews and essays, but all that lacked the dignity of pages between two hard covers. And then I heard that somebody was planning a series of biocritical studies on young adult authors, and the editor was to be a young adult specialist at Boston Public Library, Ron Brown. And I had his phone number.

I stubbed my toe rushing to call him. “Dibs!” I cried. “Dibs on Robert Cormier!” Ron gave me a thumbs-up, and so it began. The “somebody” who was doing the series turned out to be Twayne Publishers, a division of G.K. Hall and a venerable and dignified outfit that had a long history of turning out respectable literary criticism. But could they tolerate the more lively tone I envisioned for a study of a body of work read by teens? All my fears were put to rest when I met my in-house editor, Athenaide Dallett. The daughter of concert duo pianists, she was young, witty, creative, very bright, and eager to learn about young adult fiction. She had already found her beginning point in the works of Robert Cormier and was reading her way through his novels with amazed pleasure.

And “amazed pleasure” was my reaction, too, when the Cormiers graciously invited me to visit them at their home in Leominster, Massachusetts. There I interviewed Bob nonstop for two days, except for the time we spent having an afternoon beer or two and the hours I happily delved into the riches of the Cormier Archive at the Fitchburg College library. I went home and immersed myself in the subtle complexities and puzzles of his novels, and in 1985 the debut of Twayne’s Young Adult Author Series was celebrated with the publication of the first volume, Presenting Robert Cormier . The occasion was observed with speeches and a gala presentation at the Boston Public Library Authors Series and a reception and signing (by both Bob and me) at the Boston Bookstore Café. My delight in the display window full of what Bob always called “our book,” and my pleasure at speaking to an audience of distinguished Boston literati was undimmed by the fact that I had come down with the flu and had a fever of 103 as I stepped up to the podium.

Meanwhile, Series Editor Ron Brown had been lining up other people to write about the leading YA authors. In 1985 choosing the subjects was simple—YA lit had a canon of about twenty-five Big Names, and that was it. Ron recruited writers from among his friends and Boston colleagues to tackle his choice of the first six Biggies, and, encouraged by the critics’ grateful applause, settled down to encourage and edit the growing series. The second book to be published was Presenting M.E. Kerr by Alleen Pace Nilsen, who was not only already the co-author of the aforesaid Literature for Today’s Young Adults , but a past president of ALAN, a selection pattern that was to be repeated many times in the series. And then in 1986 Ron had a Thoreau-like epiphany about the shape of his life and moved on to live in the country, while I inherited the editorship of the nascent series.

Athenaide Dallett and I took over the editing of the works in progress. In the beginning we exchanged long editorial letters before we passed our thoughts on to the writers, and from her brilliance as an editor I learned how to spot the places where changes would improve a manuscript—and how to communicate those changes to a writer tactfully, with encouragement instead of criticism. Athenaide became my mentor, my staunch ally in sticky editorial situations, and to this day a valued and admired friend.

Acquisition was now in my lap, so I went straight to the top, to the Godfather of ALAN, Don Gallo. I offered him the biggest fish in my pond—Richard Peck—and he couldn’t refuse. But there was a problem. Richard didn’t want to be biographized. With becoming modesty, he demurred, explaining that he felt his writing wasn’t worthy of a whole book of analysis—an assessment, even at this point in his career, that was obviously dead wrong. Nevertheless, Don and I persisted. I wrote cajoling notes and letters (to this day one does not communicate with Richard Peck by email) and finally he agreed to be the subject of a Twayne study. Don wrote it, but in four years Richard had several more major novels and it was necessary to update the study, and now Don Gallo and co-author Wendy Glenn are about to publish the definitive work on Peck, including all the rich writing of his maturity, for Twayne’s successor series.

As I added more authors, I laid down some guidelines for the series’ detailed content and style. Our target audience was three-fold—YA librarians, teachers, and students—and so we wanted the books to be lively and readable, but to offer sound critical insights and talking points for class discussion. I also wanted the subject author to come alive as a person in these pages, and so I encouraged my writers to do personal interviews and even get themselves invited to the author’s home. “Find out the dog’s name,” I told them. “Notice the state of the writing desk. And don’t back away from the hard questions.”

From my own experience in doing hundreds of interviews for an earlier book, Passing the Hat , I wrote detailed instructions for interviewing (“unwrap your tapes before you get there . . .”). Other stylistic and practical matters were also dealt with in the Series Guidelines, such as when to refer to the subject author by first name (only in the preface) and when to use terms like “children” or “youngsters” for YAs (never). A persistent difficulty in the early days was writers’ tendency to confuse the instruction to write lively with permission to use slang and inappropriate colloquial expressions. Nowadays, that tendency has faded away and has been replaced with a different fault—stilted academic jargon and feminist rhetoric.

A stylistic problem with legal implications was Twayne’s policy of a 400-word limitation on quoted material, even from the works of the subject author. Although I stressed this matter in the Guidelines, nearly every writer exceeded the limit. I spent many tedious hours counting words and adding up the totals—and then shaking my finger at the writer. Holding quotes down was especially difficult for those working with highly quotable authors—like Richard Peck. The better the author, the more difficult it is to avoid picking up that author’s apt phrases and colorful descriptions, and to this day, the problem persists with the series. But I hasten to assure writers who grieve at the need to cut that the book will be better with their own carefully considered words.

One matter that I couldn’t change was the title format. Some people had even begun to refer to it as “the Presenting series,” so name recognition won out over style and grace. But another feature of the first two books that both Athenaide and I joined forces to alter were the clumsy drawings used as illustrations. These were universally deplored by our writers and the critics, so with the third volume, Presenting Norma Fox Mazer , we switched to photos supplied by the subject author.

As the series grew, I found that I had to change my preconception that the writers could be drawn from my ALA network of YA librarians. I found that working librarians do not have spare time to write, nor do working teachers, with a very few exceptions. However, it dawned on me that academics are expected to write, and their bosses smile on the time and effort that takes. And as I became more involved with ALAN, I realized that here was a concentrated collection of passionate and articulate supporters of young adult literature who were eager to produce books for Twayne. As I drew on this pool of writers, the series became almost a who’s who of excellence in ALAN leadership. Of the thirty-five ALAN presidents since 1983, fifteen have written books for the series, and of the fifty-nine titles in the combined Twayne and Scarecrow series, thirty were written by ALAN leadership, including both Executive Secretaries. Old ALAN hands will recognize many familiar names in the bibliographies that accompany this piece.

One of the great pleasures in editing the Twayne series was matching subject authors with congenial writers. Joanne Brown and Kathryn Lasky, two witty Jewish mothers, hit it off beautifully, as did passionate shoppers Paula Danziger and Kathleen Krull. Ted Hipple charmed me into giving him a contract to write about his fellow Tennessee author, Sue Ellen Bridgers. But perhaps my best match was Terry Davis with his college friend Chris Crutcher. Terry, as a fine YA author himself, wrote a brilliant biographical chapter in the shape of a long, fictional motorcycle journey, which I very reluctantly axed because it didn’t fit the rest of the book, but his intimate knowledge of the dynamics of Crutch’s family provided invaluable insights into the author’s work. Other joys were the unexpected discoveries that emerged about authors we thought we knew: William Sleator’s years as a ballet pianist; Barbara Wersba’s early career as an actress (with a glamour photo to prove it on the cover); the Mazers as radical political activists in their youth.

An inherent problem in trying to analyze authors in the middle of their careers is how to fit future works by that author into a current evaluation. I ran into that difficulty very early with the first edition of Presenting Robert Cormer , when I tried to gather together and interpret all his themes with what I thought was a very neat metaphor about an implacable force. But Bob read it, of course, and it made him so selfconscious that none of his later novels fit my tidy interpretation. Criticism can influence creation, for good or bad. Trying to catch up with a prolific author, too, can be a breathless race, as Gary Salvner discovered in writing about Gary Paulsen. I began to tell writers to ask to see unpublished books in production, or even books in progress.

As the series went on, I started to feel that it was getting too formulaic, and so I looked for new ideas to add to the successful basic format. Science fiction and the newly emerging genre of fantasy had troubled me because to cover these genres adequately, it would be necessary to look at many minor authors, as well as a constellation of Big Names. But it was a type of writing that I had publicly deplored, despite its popularity, that became the subject of the first Twayne series genre study with Presenting Young Adult Horror Fiction by the irrepressible Cosette Kies. SF and fantasy had to wait, the first until I found a writer fresh enough to the genre to be objective in Suzanne Reid, and the second for eight years, while VOYA editor Cathi MacRae desperately tried to organize, read, and make sense of the rapidly expanding field of fantasy. (Characteristically, Cathi insisted on including short book reviews by teens, over my initial objections but later approval)

During these years there were changes at Twayne Publishers. In 1989 Athenaide was promoted out of my reach and later left to get a Master’s degree at Georgetown University, and Liz Traynor Fowler took her job as in-house series editor. Later the position was passed to Jennifer Farthing. Between 1985 and 1989 six of the early titles were updated for a Dell paperback reprint series titled Laurel-Leaf Library of Young Adult Authors. By 1995, Macmillan had replaced G.K. Hall. And then in 1997 market pressures forced Twayne to stop acquiring new titles, and two years later Macmillan Library Reference sold to the Gale Group and the series was cancelled, despite good reviews and excellent sales.

But I was having too much fun editing “my” series to give it up, and besides, I had made promises to writers who were at work on as-yet-unpublished books for the now defunct series. So I looked around and settled on Scarecrow Press, primarily because that was where Dorothy Broderick and Mary K. Chelton had taken their essential YA magazine, Voice of Youth Advocates . Also, I had worked with Editorial Director Shirley Lambert and anticipated that she and I would see eye to eye about the series’ future. We did, and we hammered out a title: Scarecrow Studies in Young Adult Literature (although I lobbied for “Young Adult Authors and Issues”). In this new situation I made lots of room for fresh ideas, keeping the successful single author and genre formats, but also opening up a broader perspective to include issue studies and anything else that might come under the heading “YA lit crit.”

The first volume stretched my commitment to innovation. R.L. Stine was a controversial phenomenon at the time for his wildly popular Goosebumps and Fear Street paperbacks, and the brilliant and unpredictable Patrick Jones wanted to use Stine as a jumping-off place to examine the value of literary popular culture. This struck me as a great book idea, even though I personally abhor trashy popular horror fiction. So I wrote Patrick, “I will take care not to step on your opinions, as long as you justify them.” And then I added, “I think we’re going to have some fun with this.” And we did, as we argued back and forth in the margins of the developing manuscript. In 1998 What’s So Scary about R. L. Stine was published as the first volume in the new series, sporting a new look with a laminated designer cover and, instead of internal family snapshots as illustrations, a truly scary photo of Stine, warts and all, as a frontispiece.

During the writing of the book, Patrick and I had scoured our networks to find a way to get an interview with Stine, but the walls protecting him held firm. With the help of an editor friend I even had a carefully composed letter carried into the fortress and hand-delivered to Stine’s wife, but there was no response. Then, weeks after the book was published, Patrick got an email from Stine, thanking him and praising the book lavishly. “I had no idea such a work was in the works,” he wrote. “Why didn’t you and I ever get to talk?” We gnashed our teeth.

Chris Crowe had had better luck in getting to the notoriously reclusive Mildred Taylor, but his fine study of that author stayed behind at Twayne and became the last book in that series. The Scarecrow series began to grow and gain good reviews, in spite of a bumpy time with the second book. As the completed manuscript of Jeanne McGlinn’s Ann Rinaldi: Historian and Storyteller went into production, a huge controversy exploded over Rinaldi’s depiction of government Indian Schools in her novel My Heart Is on the Ground. “Hold the press,” I shouted. McGlinn, at my request, rewrote her analysis of that book and added an acknowledgement of the issues raised by Native American advocates, especially Deborah Reese, who had written a scathing review, and Beverly Slapin, editor of the website Oyate. But some good came out of this brouhaha, as out of it emerged the right person to do an entire book on the now obviously sensitive issue of Native Americans in YA lit—Paulette Molin.

As the series developed, I continued to select leading authors as subjects of studies. Arthea Reed (Charlie to her ALAN friends) was a logical choice to write about Norma Fox Mazer, since she knew the couple’s history through her Twayne book on Harry Mazer. Edith Tyson gladly took on Orson Scott Card instead of the book on YA Christian fiction in which she had bogged down. I made sure David Gill understood surfing and Hawaiian culture before assigning him to write about Graham Salisbury. Ten other authors were captured for the series, but still there were some who eluded me, either because they felt the time was not right for them, or because I continued to search for exactly the right writer.

Studies of broad YA literary issues more and more became a strong component of the series—empowered girls, sports, humor, guys, historical fiction, and a delightful discussion of names in young adult novels, a subject Alleen Pace Nilsen had wanted to write about since her Twayne book on M.E. Kerr. Forthcoming titles will tackle the growing YA theme of mixed heritage, explore the history of girls’ series books, take a hard look at body image and female sexuality, and discuss serious issues of the depiction of animals in YA lit.

An obvious subject need was a book on GLBT characters and themes, and the obvious person to write it was the great Michael Cart. For years he was interested, but too busy. I waited. Finally, in 2006, he and co-author Christine Jenkins produced the definitive book on gay and lesbian issues in YA lit— The Heart Has Its Reasons —and it quickly became our bestseller. And one book that defied classification was Lost Masterworks of Young Adult Literature . Its editor, the magnificently organized Connie Zitlow, was inundated with offers from well-known YA writers and critics to sound off in essays about their own favorite forgotten titles.

Marc Aronson

Talking with renowned editor Marc Aronson one day, I had an epiphany. “How would you feel about doing a collection of your essays and speeches?” I asked. He felt fine about it, and the two books in which he gathered his audacious and literate writings became steady sellers for Scarecrow. Emboldened by this success, I asked Michael Cart for a collection of his articles and essays, and although his “Cart Blanche” columns were already spoken for by Booklist, he put together a thoughtful and enjoyable compilation, Passions and Pleasures . And now I am thinking of looking over my own short pieces for a Scarecrow volume, which I may title Campbell’s Scoop.

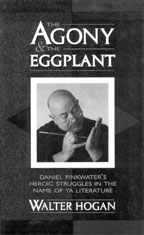

Perhaps the most fun I had with editing the series came with Walter Hogan’s delicious book about the quirky comic genius, Daniel Pinkwater. As chapters arrived in the mail, I could’t resist tearing open the manila envelope on the way home from the mailbox, to delight in the latest installment of Hogan’s droll discussion of Pinkwater’s equally droll novels, with voluminous and amusing footnotes. Walter was in close touch with Pinkwater all along, so when it came time to choose a catchy title, it was Pinkie’s suggestion of The Agony and the Eggplant that caught my fancy with its sheer absurdity. But would my editor Shirley buy it? I ran it past her, and there was a long, thoughtful silence. Then she smiled. “I love it!” she cried. However, Pinkwater’s choice of a cover—himself with five rhinoceroses—was just too far out, and so we settled for a photo in which the large author is painting a picture on his own palm.

YA literary criticism has come a long way since 1983. Several publishers are now doing excellent author studies of one shape or another, and there have been many useful annotated bibliographies of various subjects. It can be said in all honesty that there is now lots of serious literature about young adult literature. And lots more to come as the genre grows beyond our wildest predictions. As I look over my list of works in progress for Scarecrow Studies in Young Adult Literature, I think I can promise that we will continue to pounce on the best new authors, tear open the most challenging issues, and spring a surprise or two.

- Presenting Robert Cormier by Patty Campbell. 1985, updated ed. 1989. Dell pbk 1990.

- Presenting M.E. Kerr by Alleen Pace Nilsen. 1986, updated ed. 1997. Dell pbk.1990.

- Presenting S.E. Hinton by Jay Daly. 1987, updated ed. 1989. Dell pbk. 1989.

- Presenting Norma Fox Mazer by Sally Holmes Holtze. 1987. Dell pbk. 1989.

- Presenting Rosa Guy by Jerrie Norris. 1988. Dell pbk. 1992.

- Presenting Norma Klein by Allene Stuart Phy. 1988.

- Presenting Paul Zindel by Jack Jacob Forman. 1988.

- Presenting Richard Peck by Don Gallo. 1989. Dell pbk. (rev. ed.) 1993.

- Presenting Sue Ellen Bridgers by Ted Hipple. 1990.

- Presenting Judy Blume by Maryann N. Weidt. 1990.

- Presenting Zibby Oneal by Susan P. Bloom and Cathryn M. Mercier. 1991.

- Presenting Walter Dean Myers by Rudine Sims Bishop. 1991.

- Presenting William Sleator by James E. Davis and Hazel K. Davis. 1992.

- Presenting Young Adult Horror Fiction by Cosettte Kies. 1992.

- Presenting Lois Duncan by Cosette Kies. 1993.

- Presenting Madeleine L’Engle by Donald R. Hettinga. 1993.

- Presenting Laurence Yep by Dianne Johnson-Feelings. 1995.

- Presenting Ouida Sebestyen by Virginia R. Monseau. 1995.

- Presenting Paula Danziger by Kathleen Krull. 1995.

- Presenting Robert Lipsyte by Michael Cart. 1995.

- Presenting Cynthia Voigt by Suzanne Elizabeth Reid. 1995.

- Presenting Gary Paulsen by Gary M. Salvner. 1996.

- Presenting Lynn Hall by Susan Stan. 1996.

- Presenting Harry Mazer by Arthea J. S. Reed. 1996.

- Presenting Chris Crutcher by Terry Davis. 1997.

- Presenting Avi by Susan P. Bloom and Cathryn M. Mercier. 1997.

- Presenting Phyllis Reynolds Naylor by Lois Thomas Stover. 1997.

- Presenting Kathryn Lasky by Joanne Brown. 1998.

- Presenting Barbara Wersba by Elizabeth A. Poe. 1998.

- Presenting Young Adult Science Fiction by Suzanne Elizabeth Reid. 1998.

- Presenting Young Adult Fantasy Fiction by Cathi Dunn MacRae. 1998.

- Presenting Mildred Taylor by Chris Crowe. 1999.

- What’s So Scary about R. L. Stine? By Patrick Jones. 1998.

- Ann Rinaldi: Historian & Storyteller by Jeanne M. McGlinn. 2000.

- Norma Fox Mazer: A Writer’s World by Arthea J. S. Reed. 2000.

- Exploding the Myths: The Truth about Teenagers and Reading by Marc Aronson. 2001.

- The Agony and the Eggplant: Daniel Pinkwater’s Heroic Struggles in the Name of YA Literature by Walter Hogan. 2001.

- Caroline Cooney: Faith and Fiction by Pamela Sissi Carroll. 2001.

- Declarations of Independence: Empowered Girls in Young Adult Literature, 1990-2001 by Joanne Brown and Nancy St. Clair. 2002.

- Lost Masterworks of Young Adult Literature , edited by Connie S. Zitlow. 2002.

- Beyond the Pale: New Essays for a New Era by Marc Aronson. 2003.

- Orson Scott Card: Writer of the Terrible Choice by Edith S. Tyson. 2003.

- Jacqueline Woodson: “The Real Thing” by Lois Thomas Stover. 2003.

- Virginia Euwer Wolff: Capturing the Music of Young Voices by Suzanne Elizabeth Reid. 2003.

- More Than a Game: Sports Literature for Young Adults by Chris Crowe. 2004.

- Humor in Young Adult Literature: A Time to Laugh by Walter Hogan. 2005.

- Life Is Tough: Guys, Growing Up, and Young Adult Literature by Rachelle Lasky Bilz. 2004.

- Sarah Dessen: From Burritos to Box Office by Wendy J. Glenn. 2005.

- American Indian Themes in Young Adult Literature by Paulette F. Molin. 2005.

- The Heart Has Its Reasons: Young Adult Literature with Gay/Lesbian/Queer Content, 1969-2004 by Michael Cart and Christine A. Jenkins. 2006.

- Karen Hesse by Rosemary Oliphant-Ingham. 2005.

- Graham Salisbury: Island Boy by David Macinnis Gill. 2005.

- The Distant Mirror: Reflections on Young Adult Historical Fiction by Joanne Brown and Nancy St. Clair. 2006.

- Sharon Creech: The Words We Choose to Say by Mary Ann Tighe. 2006.

- Angela Johnson: Poetic Prose by KaaVonia Hinton. 2006.

- David Almond: Memory and Magic by Don Latham. 2006.

- Aidan Chambers: Master Literary Choreographer by Betty Greenway. 2006.

- Passions and Pleasures: Essays and Speeches about Literature and Libraries by Michael Cart. 2007.

- Names and Naming in Young Adult Literature by Alleen Pace Nilsen and Don L. F. Nilsen. 2007.

- Sisters, Schoolgirls, and Sleuths: Girls’ Series Books in America by Carolyn Carpan.

- Richard Peck by Don Gallo and Wendy Glenn.

- Sharon Draper by KaaVonia Hinton

- Mixed Heritage in Young Adult Literature by Nancy Reynolds. Feb. 2009.

- Reading Russell Freedman by Susan P. Bloom and Cathryn M. Mercier.

- Janet McDonald by Catherine Ross-Stroud.

- Animals and Animal Rights in Young Adult Literature by Walter Hogan.

Patty Campbell is a longtime YA critic, lecturer, and writer, and the winner of both ALA’s Grolier Award and the ALAN Award. In 2005 she was the president of ALAN and chaired the Workshop.