JARS v42n2 - In Search Of Rhododendrons In Nepal

In Search Of Rhododendrons In Nepal

Bill Jenkins, Los Angeles, California

In 1974 I joined the American Rhododendron Society in order to get otherwise unobtainable plants. This was accomplished in a few years, but I have stayed on. I like rhododendron people. Also, the ARS connection provides an excuse to travel at the most beautiful time of the year, around May 1st. This travel has taken me to places which have always seemed interesting but which I would have missed otherwise, faraway places with strange sounding names, like Atlanta, Cleveland, and Seattle. In April, 1987, I traveled to Kathmandu, in search of the rhododendron species that are native to Nepal.

This trip started with an ad in the Sierra Club newsletter, regarding a twenty two day trek, all transportation and living expenses included, for $2,240. I called Nepal Tours and asked if there would be rhododendrons. The voice said, "all over". I assumed this meant "all over Nepal". As time went on, I learned the correct interpretation: "the existence of the Rhododendron arboreum forest in Nepal is almost all over".

Research

I telephoned two ARS members who had visited Nepal and asked about the blooming season. One had not been there "in season". The other said it all depends on altitude. In the handbook,

Trekking in Nepal

, author Bezruchka says they bloom in January. (Actually, when 'Loderi King George' is blooming in Seattle, the

R. arboreum

forest is blooming in Nepal.)

In Kathmandu, I hired a guide and a taxi driver to take me to the Royal Botanical Garden. They both spoke fair English, so I attempted a conversation about rhododendrons. Nothing. But they did know about Madonna, the rock singer, and wanted to know more. I couldn't help. Each of us admired one feature of the other's country, but the admiration was not mutual.

It was not much better with the Director of the Garden, a transplanted Indian. I showed him a map of the route I would be taking and asked for pointers. He wished me luck; said he had no knowledge of the area, and suggested purchasing the book, Catalogue of Nepalese Vascular Plants . This publication lists twenty eight native species, but does not describe them or say where they grow. So much for research.

The Journey

On the way to Nepal, I spent four days sightseeing in Hong Kong, where they have the best of both worlds, ancient, yet ultra modern. We spent a day in Canton, an anthill were swarms of sober people who all look alike go rushing with grim determination to their destinations.

In Kathmandu, our group viewed ancient shrines and temples for two days. Buddha was born in Nepal in 563 B.C. Also, the holy river of India, the Ganges, originates here.

We took a plane flight along the Himalayan Barrier range, which includes Mt. Everest. Since we were above the clouds, these serene peaks were visible in all of their glory. Later, while hiking among them, they were usually obscured from view.

We started the trek in Toyotas, which took us forty miles to the end of the road. After that, everything was on foot. No mechanized vehicles, no telephones, no electricity. We were eight porters, three cooks, and Sherpa guide, and three trekkers.

At first, the landscape was tropical with wild monkeys and bananas. By the fifth day we had reached 5,000 feet. Near the village of Chame, I spotted my first rhododendron, a brilliant red R. arboreum . One side branch had been spared on a clear-cut hillside of stumps, 5 to 10 inches in diameter. Sensibly, the 2 foot stumps had been left in place to lessen erosion on the steep incline. Hopefully, new shoots will grow into another grove.

As in all of my travels to view rhododendrons, going is so enjoyable that at some point along the way the thought comes, "This is so great. Even if I don't see any rhododendrons, the trip will have been a success". This was, more then ever, true in Nepal. The landscape near the roof of the world is fantastically beautiful. We followed a trade route established between India and Tibet in pre-Christian times. Frequent springs coming out of the mountains make life possible in a constant series of villages, strung like beads along the trail. Farm terraces are spring irrigated. The natives were friendly and attractive. In case of nuclear disaster, these lucky people will probably survive because of their isolated, self-sufficient existence.

We traveled in a caste system. The Sherpa guide was the undisputed boss. The head cook, who looked Chinese, was second in charge. He carried no load and spoke six languages, learned from tourists. His two boy assistants carried light loads, had legs like mountain goats, and usually led the way. Our Sherpa guide maintained a central position in this strung out safari in order to watch over everyone. The eight porters suffered no indignity from the fact that they carried loads as big as themselves. Theirs is a respected, indispensible, profession. They were quiet, camped apart, and ate separately.

We paying customers were the royalty. I have never been so pampered. The Nepali vegetarian fare was delicious and nutritious. Importantly, our drinking water was boiled 20 minutes and the food was well cooked. We had no sickness within our group, fortunate in a country where exotic parasites lurk in untreated water and food. We met sick travelers along the way who had not been cared for so well. We exercised for six to eight hours a day. This, plus good food, ten hours of sleep at night, no logistic worries, and beauty everywhere, was conducive to good health and a sense of well-being.

We circled the Annapurna range, with Dumrye at the beginning and Pokhara at the end of a horse-shoe trail. This necessitated going over the 17,500 foot Thorung pass. It is here that the Annapurna and Barrier ranges come together. On the day of the big push, we started at three am, because by noon wind would make travel impossible. My fingers were numb even beneath two pairs of mittens. At one point, the trail (obscured by fresh snow) crossed a glacier, where a sheet of ice sloped sharply into eternity. Each step had to be first probed with a staff to prevent stepping off the trail onto air. Finally, there was a half-hour of switch-backing up the face of the mountain. Snow was up to the knees, to get enough oxygen required rapid and laborious deep breathing. I reached the summit at eight am and waited, thanking my legs for not failing; then suddenly became ecstatic over the fact that I was still alive. The head cook arrived and told me to start down the other side.

|

|

R. arboreum

forest, Poon Hill, Ghorepani

Photo by Bill Jenkins |

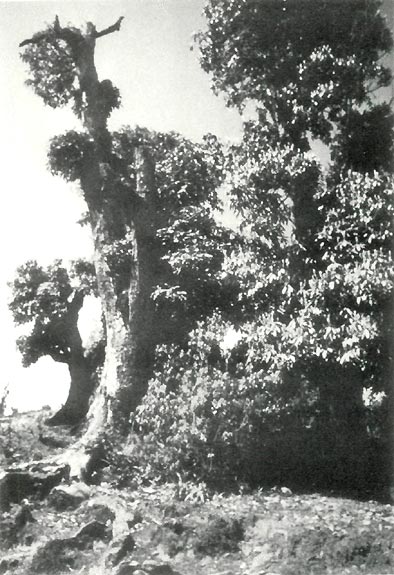

Mission Accomplished

Four days after Thorung pass, we had descended to 4,500 feet and arrived at Ghorepani. Here, at Poon Hill, is a forest of 80 foot tall rhododendrons. Some of them are 250 years old. This was not a horticulturally oriented trek. No one else cared. We were not supposed to stop at Ghorepani, but by some miracle, our Sherpa guide became ill. It may have been a plot. He knew I wanted to spend time here, and the others were determined to press on. We made camp at two pm and stayed the night.

I met an Englishman who had visited here twice before and was organizing a climb next morning to view sunrise on the Annapurna peaks. Nevertheless, I decided to climb to the top on this late afternoon. I lost the trail several times, but kept working up through the forest until the trail reappeared. This was the best thing I could have done, because it led me through forest still in a natural state. R. arboreum was the dominant tree.

On the steep hillside were monstrous specimens with the bulk of the blue gum eucalyptus found along old California roads. The R. arboreum were in peak bloom, with white, pink, and red flowers. A note in my diary describes this as one of the happiest days in my life. I guess it was. All of the best pictures were obtained on this climb. The top of Poon Hill looks like the opening scene in "Sound of Music". In both the movie and Poon Hill, the hilltops have been cleared and turned into grassland. However, at Poon Hill, the tree tops which come up from the steep hillsides are not pine, but rhododendron - in glorious bloom on April 18, 1987.

Next morning we were fog bound. The group climb was cancelled. I went up anyway. By now, I knew the trail. At the top, the fog lifted a few times, so I got more pictures. Of course, it is because of fog and damp that rhododendrons evolved in this place, not because of sunny weather. The trunks of these noble giants were covered with moss and other epiphytes. A vast line of mountain shapes extended dimly through the mist, like a Chinese painting.

That night I met a man who looked like Abraham Lincoln, Bill Jones. He works in cooperation with the Annapurna Conservation AREA Project, a Nepal non-government organization. He is Australian, of Welsh descent. Jones first saw Ghorepani in 1975 when the rhododendron forest extended for miles. Returning in 1985, he was horrified to find only a fringe left, around Poon Hill. He was so concerned that he stayed on and became leader of the local conservation and health effort. Among other good works, he has brought down a pure water supply from high in the mountains for the villagers, and has started a nursery for re-establishing thirty-two plant species, including rhododendrons.

|

|

Just to make sure they don't grow back

Photo by Bill Jenkins |

The Problems

Legally, the mountains and forest are owned by the King, but poaching is a way of life. Trees are the only source of fuel. In 1975 there was one lodge for tourists. Collection of dead wood for fuel was sufficient. Today, there are eight lodges, lots of tourists, and they need fuel, mostly for cooking. Unlike Americans, the natives do not clear-cut. Instead they just cut random stumps and piles of kindling, constantly nibbling away at the forest. A chain saw can fell a 250 year old

R. arboreum

in a few minutes.

I was alarmed to find no seedlings growing. Bill Jones explained that horse caravans often spend the night here. The animals are turned loose to graze. They eat the seedlings. Less destructive is the old practice of pruning for fodder. Women and children spend much time collecting and bundling any branches within reach, which they bring home to feed their animals. Water buffalo cows give rich milk. The bulls provide meat.

Mr. Jones says the whole conservation effort is funded by foreign countries. Otherwise, he has had excellent cooperation from the villagers. More than 400 have donated their labor, wherever needed, to develop his projects. They are worried about the obvious deterioration of their environment.

At this point, it is an ongoing struggle of education and work, with not very impressive results. Bill Jones will be leaving at the end of 1988. He says that international pressure is the key, and that the most effective pressure point for protest is the Ministry of Tourism; Department of Tourism; Tripuresway, Kathmandu, Nepal.

|

|

R. arboreum

can survive severe pruning

Photo by Bill Jenkins |

The Answers

Some things that could help:

1. Make it mandatory for visa holders to carry enough kerosene for their fuel needs. (Butane is useless at this high altitude.) Carrying it in is easy. There is an oversupply of porters who will gladly carry 80 pounds for the equivalent of $3.50 per day.

2. Encourage trekkers to double up on cooking sites. By the time a campfire gets going well, the meal for the first group is cooked. Others should be ready to start their meal, using the same fire.

3. Prune trees instead of cutting them to the ground. Make it mandatory that stumps five feet high be left, with bark intact. New tops will grow.

4. Establish an inviolable parkway for fifty feet on either side of the main trails near Ghorepani. This will at least leave a remnant of natural forest for future tourists to see.

5. Recognize the importance of tourism in the Nepal economy. Knowing that potential income from a large segment of tourists (rhododendron people) will be lost if the R. arboreum forest is destroyed will generate interest in conservation.

6. Petition the King to make Poon Hill an international monument. Post a military guard, or a forest ranger in the hilltop tower, which is already in place, to discourage poaching.

|

|

Rhododendron massacre

Photo by Bill Jenkins |

Travel Advice

If you are planning a trip to see rhododendrons in Nepal, don't delay. Time is running out. If you go, you will arrive and depart at Kathmandu, the only place where large planes can land. When you have finished with Kathmandu, forget the Thorung pass. Go directly to Pokhara. If possible, use the excellent military highway, which takes only six hours. From Pokhara, it is a three or four day hike up hill to Chorepani; two days to come back down. Feel free to contact me, Bill Jenkins, for further information.

When you have finished with Nepal, consider Agra and the Taj Mahal. It would be sad to travel half way around the planet to view one of the world's treasures and miss another which is close by. (I did, because I thought the Taj was too far south.)

On the way home, Bangkok should not be ignored. This is a major departure place for transpacific jets. To me, Thailand was an unexpected delight. If there was ever a garden of Eden, this must have been it. I stayed for four days of sightseeing. Frequent tropical showers washed everything clean, producing a greenhouse atmosphere in which all living things thrived. The people looked young, clean, and healthy. All life seemed in balanced harmony. Maybe it has to do with the Buddhist faith. I learned that Buddha was a teacher, not a god. He taught a way of life that is good for the community and pleasant for visitors. One of his most interesting ideas is using love to get rid of an enemy.

Along the rivers and canals of Bangkok are many picturesque, well preserved Buddhist temples, a daily part of the lives of the people. At the Grand Palace, there are acres of the most exquisite temples and monuments ever conceived. Ghosts of Anna and the King of Siam still dance in the ballroom.

Help!

If travel is out of the question, you can still do something which may be more important. Write a letter of protest if you feel concern for the

Rhododendron arboreum

forest of Nepal. Express your own thoughts. Your ideas may be better than mine. Tell it to the Department of Tourism.

There are more than five thousand members in the ARS. If this account could inspire one thousand letters of protest and suggestions, it would really help. Most of the people in Nepal are poor and helpless to do anything about conservation, even if they were knowledgeable, which they are not. The government agencies are strong and can make changes, particularly, if it is good for business. The fact that you are an ARS member says that you are a special kind of person. If you have strong feelings about conservation in Nepal, express them today, in writing. A 44¢ stamp will deliver a one page letter to the only place that can cause reform: The Ministry of Tourism; Department of Tourism; Tripuresway, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Bill Jenkins, President of the Southern California Chapter, is also the Alternate Director for ARS District Five. He has presented a slide show about the destruction of the rhododendron forest in Nepal to several western chapters.