JARS v53n2 - Providence Canyon: The End of the Trail

Providence Canyon: The End of the Trail

L. Clarence Towe

Walhalla, South Carolina

Because of several past geologic events, Atlanta, Ga., has the enviable distinction of being near the epicenter of the Eastern seaboard's widespread native azalea population. With the recent confirmation of Rhododendron vaseyi on the Rabun Bald in the northeastern corner of the state, 12 of the 14 East Coast species are native to Georgia, leaving only R. canadense and R. prinophyllum to be found outside the state.

In addition to the species, there are many areas with colorful hybrids, some of which are more intensely pigmented than the parent species. Hybrids are common in Georgia, and in several nearby states, in all pair-wise combinations where two or more species flower at the same time and whose ranges overlap. Some hybrid groups are very complex, perhaps involving as many as four or five species. Even Rhododendron calendulaceum , the tetraploid outlaw of the gang, often gets into the act, most frequently with R. periclymenoides . Only the reclusive R. vaseyi has prudishly chosen to remain ethnically pure, again demonstrating that virtue is its own reward.

To see what Georgia has to offer will require visits to Rhododendron austrinum sites near the Florida line in early March and will end over 300 miles to the north at 5,000 feet (1500 m) in the southern Appalachians in late July. Just as the last R. arborescens and R. cumberlandense are dropping their flowers there, the final late show is beginning along the mid-Georgia/Alabama line, almost back to where it began in March. Here in a few scattered sites near the Chattahoochee River, R. prunifolium puts on a show of orange-red to red that begins in early July with the peak bloom period being late July.

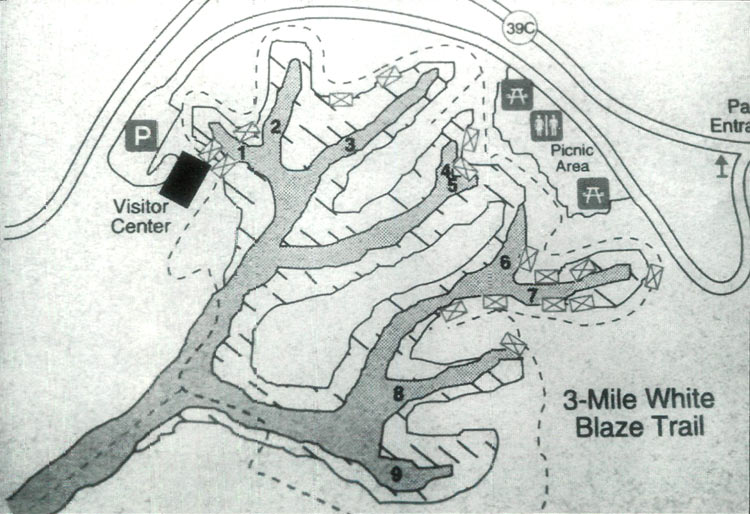

One of our best azaleas, Rhododendron prunifolium , the plumleaf azalea, is unique in that it grows in a very restricted area and flowers as late as September. Perhaps the premier place to see this species is at Providence Canyon State Conservation Park near the small town of Lumpkin in south-central Georgia. Referred to as "Georgia's Little Grand Canyon," this spectacular land form is located in remote pastoral countryside that is an easy day-trip from Atlanta. The park is equipped with exhibits of geologic artifacts found in the canyon, as well as with maps and food. The well-maintained three-mile trail into the nine dead-end forks of the canyon and around the rim is easy and can be completed in a few hours.

To stand on the rim and look down into the canyon while surrounded by typical southern farmland is like looking through a doorway into another dimension. To know that coyotes and armadillos inhabit the area adds to the feeling of being out West. Why such a unique land form is there is well documented and easy to understand, although the marine fossils it uncovers as it grows and its ultimate size pose more thought-provoking questions.

The canyon began in the early 1800s as a result of erosion following deforestation of the area by local farmers. By 1850 there were gullies 5 feet (1.5 m) deep. This process continues today, with some of the canyons being 150 feet (45 m) deep. The nine main forks of the canyon are lengthening by a process known as "headward erosion" while they widen by lateral erosion, both of which are caused by rainfall. The canyon has eroded through the thin red clay topsoil common to the region and through a deep, sandy sea-bed layer known as the Providence Formation, for which the canyon was named. The harder clay of the Ripley Formation, through which it is now eroding, has slowed the process and may eventually control the depth of the canyon.

|

|

Providence Canyon

Photo by L. Clarence Towe |

The well-used trail from the visitor's center into the canyon goes through a mixed hardwood forest of oaks and hickories. After a descent of some 150 feet (45 m) to the floor at the lower end of the canyon, the stream that should be there appears as a 50-foot (15 m) wide river of damp, reddish brown sand in the heat of August. The sand is firm enough to walk on, though it is apparent from its sponginess that underground water is moving through it. The riverbed is always clean, because the area is being well maintained by park employees and by the occurrence of torrential gully-washers that can temporarily drop the level of the lower canyon floor by as much as 6 feet (1.8 m). Normal precipitation after periods of heavy rainfall washes more up-slope sand into the canyon and returns it to its present elevation.

|

| Providence Canyon State Conservation Park |

By walking northward either clockwise or counter-clockwise from the point where the trail crosses the lower canyon floor, the nine dead-end forks of the canyon can be explored without leaving the damp stream bed. The sandy gray soil of the lower slopes of the canyon walls contrasts sharply with the red sand of the canyon floor. It is in this narrow, damp transition zone that Rhododendron prunifolium , R. minus , and a few R. arborescens have found a temporary niche in a changing landscape. Here R. prunifolium lines the stream beds, leaning outward toward the sun, to heights nearing 20 feet (6 m). The few scattered plants that have salmon or light pink flowers are probably ( R. arborescens x R. prunifolium ) hybrids.

After meandering through the canyons, the trail leads up and out to the rim. Here the trail has protective guardrails and provides a close-up view of the magnitude of the canyon and the amount of soil removed by rainfall in less than 150 years. Along the rim trail short-leaf pines ( Pinus echinata ) and loblolly pines ( Pinus taeda ) lean outward as if in anticipation of the next storm that may send them to the canyon floor below. Some are lucky and survive the fall with root balls intact, though not usually in an upright position, and slowly grow curved trunks as they reposition themselves and try to survive.

Few azalea sites of any species are as spectacular as Providence Canyon, which, in its own unique way, rivals Gregory Bald and Roan Mountain, Tenn., and the Blue Ridge Parkway in North Carolina and Virginia. The extensive plantings of Rhododendron prunifolium at Callaway Gardens at Pine Mountain, Ga., flower at the same time as those in Providence Canyon. With some planning, both sites can be visited in one day. Together these two sites probably comprise the majority of sites with the remaining plants of this valuable late species.

Clarence Towe is a member of the Azalea chapter.