JARS v61n3 - Two Summers in the Canadian Rockies

Two Summers in the Canadian Rockies

Peter Kendall

Portland, Oregon

|

|

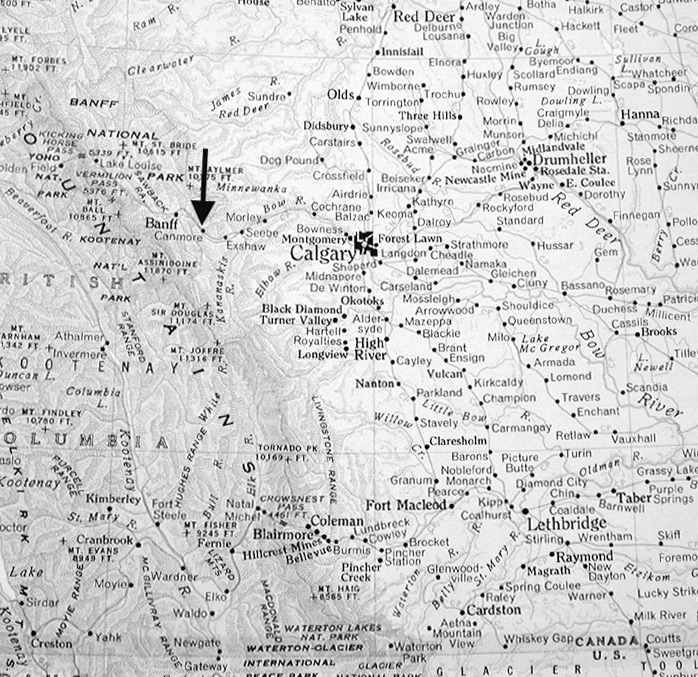

Map showing location of Canmore, Alberta,

approximately 60 mile

west of Calgary on the cusp of the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains. |

The stretch of the Rocky Mountains (from west and slightly south of the resort town of Canmore) in Assiniboine Provincial Park to the northern reaches of Yoho National Park in the province of British Columbia yields so much in the way of geological and horticultural intrigue. The geological spectacle of the Canadian Rockies takes away one’s breath. It invites the question: from when, where and how did such magnificence come to be? To ever so briefly respond to the query, I offer the following sketch.

|

|

|

||

|

Mt. Assiniboine: rock,

ice

and Lake Magob. Photo by Peter Kendall |

Mt. Assiniboine, the Matterhorn

of the

southern Canadian Rockies. Photo by Peter Kendall |

Block faulting below Mt. Yukness at

Lake O'Hara.

Photo by Peter Kendall |

Some 180 million years ago, with the break up of Pangea, the North American Plate consisted of the granitic Canadian Shield in the east and a rather rolling, non-descript western rampart ending where the Rockies’ main range is today. To the west lay the Pacific Oceanic Plate with its far-flung terranes (major island land masses) moving inexorably east and eventually into and under the North American Plate. This occurred between 120-60 million years ago during the Cretaceous Period and represents the orogeny (mountain building) of the Canadian Rockies we see today.

|

|

|

|

Mt. Rundle, Banff's signature mountain,

in Canadian Rockies

Front Range - a classic thrust fault. Photo by Peter Kendall |

Lake MacArthur and Mt. Biddle at

Lake O'Hara area in

Yoho National Park in the Canadian Rockies Main Range. Photo by Peter Kendall |

|

|

|

|

Rock Island in Sunshine Meadows,

approximately west/northwest

of Banff in Canadian Rockies Front Range. Photo by Peter Kendall |

Three Sisters mountains at dawn, Canmore's

signature peaks.

Photo by Peter Kendall |

It was only relatively recently (from some 2 million years to 10,000 years ago) during the ice ages of the Pleistocene that the present-day sculpture emerged. The 700 million-year-old rock or substrate that was uplifted was primarily sedimentary and came from ocean sediments to the west, chiefly organic carbonate (calcium and magnesium carbonate from precipitating marine organisms) and from clastic, nonorganic sediments (colloidal clay particles to large rocks) to the east. Two parallel ranges were thrust upward to heights approaching 10,000 to 12,000 feet. To the east, we see the slip faulting of the Front Range; to the west we observe the block faulting of the Main Range. Over the years, with the breakdown and deposition of materials into rudimentary soil and the ensuing climatic shifts, we find the wealth of plant material extant today.

|

|

|

|

Rhododendron groenlandicum

(formerly

Ledum groenlandicum

) at Lake O'hara.

Photo by Peter Kendall |

Rhododendron albiflorum

on

Iceline Trail.

Photo by Peter Kendall |

With forests of spruce, fir and larch, with many species of willow and similar deciduous and evergreen colonizing species (think ericaceous - including rhododendrons probably 40-50 million years ago - among them), many niches for plant material were created. From high alpine reaches to lower meadow environments, the disparate flora is astounding. Accompanying this article are photographs of some of the more spectacular geological sites and remarkable flora from locations I visited.

|

|

|

|

Draba paysonii

Photo by Peter Kendall |

Bronze bells

(

Stenanthium occidentale

).

Photo by Peter Kendall |

Peter Kendall is a frequent contributor to the Journal and a member of the Portland Chapter.