JVER v28n3 - Entrepreneurial Careers of Women in Zimbabwe

Entrepreneurial Careers of Women in Zimbabwe

Lisa B. Ncube

Ball State University

James P. Greenan

Purdue UniversityAbstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate the pathways of entrepreneurial career development and the processes involved for women to become entrepreneurs in Zimbabwe. Women entrepreneurs were studied to gain an understanding of why women chose self-employment and how local enterprise programs should be designed to benefit them. The study examined how women's experiences, the environment, and other contextual factors have assisted to shape women's entrepreneurial careers; and examined programs and policies for supporting skill and technology acquisition and development in small and medium enterprises. It was the intention of the study was to identify the priority needs of individual women entrepreneur .

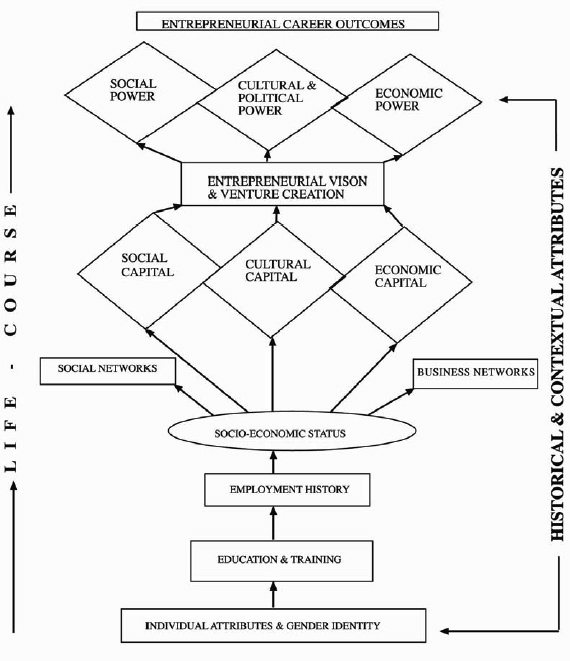

A hermeneutic phenomenological life-course approach to women's careers in Zimbabwe was used to investigate entrepreneurship. This holistic approach captured the complexity of women's entrepreneurial careers. Accumulating various forms of economic, social, and cultural capital facilitated the development of entrepreneurial careers. Women's agency or the ability to carry out initiatives was critical to overcoming social and economic subjugation in the colonial and post-colonial states. Entrepreneurial outcomes included gain in capital and power as well as construction and acquisition of skills. In addition, women entrepreneurs became increasingly visible as they developed more power within society. Technology played an important role in the development of enterprises.

Introduction

Although the economy of Zimbabwe has experienced an annual growth of approximately 4% since independence in 1980, the 1990's and the 2000's have been difficult for the Zimbabwean economy. Economic indicators have fluctuated throughout the decade. The introduction of the World Bank's and International Monetary Fund's Economic Structural Adjustment Program (ESAP) in 1990, and Zimbabwe Program for Economic and Social Transformation (ZIMPREST) in 1995, led to a negative impact on the economy. Droughts in 1992 and 1995, and the economic prosperity of neighboring countries, caused the gross domestic product (GDP) of Zimbabwe to decrease during those years. Unemployment figures have continued to increase over 60%. While short- and medium-term prospects for reversing the negative economic trend appear bleak, the small and medium enterprises sector offers some hope.

Limited opportunities in the formal sector and high unemployment rates in many African countries have resulted in increased attention on the small enterprise sector ( Daniels, 1998 ). In Zimbabwe, a large source of employment has been, historically, in the formal sector. However, with unemployment figures rising and the economy in turmoil, the informal sector has become a very lucrative source for many Zimbabweans. Although, the position of the small and medium enterprises is not clearly defined as to whether it belongs to the formal or informal sectors, its importance in economic development has become increasingly evident since independence. There has been a significant commitment by government and other organizations to elevating the role of small and medium enterprises. In addition to its importance in creating employment, the small and medium enterprises sector contributes significantly to economic growth and equity.

It is undeniable that women entrepreneurs are major actors and contributors to economic development and are becoming increasingly visible in the local economies of developing countries. The rapid growth of women entrepreneurs represents one of the most significant economic and social developments in the world; although, inadequate attention has been focused on the study of women in small and medium enterprises (SME), especially in developing economies. Research on the entrepreneurial career development of women in general and, in small and medium enterprises in particular, has been minimal. Concurrently, small business ownership has become increasingly important as an area for female economic achievement in developed and developing economies. Insufficient research on women's enterprises, in developing countries, including Zimbabwe, has resulted in a lack of wellarticulated women's entrepreneurial development policies and programs.

Entrepreneurial activities are gendered in terms of access, control, and remuneration ( Spring & McDade, 1998 ). However, the current understanding of an entrepreneur's life is primarily a male-dominated understanding of his public world and working life ( Burgess-Limerick, 1993 ). A further limitation is that most studies do not focus on women, but include them incidentally in the data and then desegregate the analyses by gender. Women in Development (WID) research contends that growth-oriented strategies, used in many studies, exclude women ( Dignard & Havet, 1995 ). Women's enterprises are viewed as small, marginally profitable, and offering minimal potential for contributing to the macro-economy. The importance of women's incomes to human capital investment and family welfare is largely ignored. Characterizations of women enterprises as small and generally lacking potential for growth ignore the work that has been completed in transforming women's traditional activities into dynamic and productive ones. These characterizations misguidedly suggest to policy makers and international donor agencies that women's enterprises are not worthy of attention ( Downing, 1995 ).

There is a paucity of theories that explain the paths of entrepreneurial career development, women entrepreneurs, and the process of entrepreneurship ( Katz, 1994a ). Theories that relate to developing countries are even more limited. It is not obvious from the literature that the experiences of women in small and medium enterprises in Zimbabwe, are documented let alone understood, and whether these experiences are attributable to entrepreneurial ventures. It is crucial that research investigates the scope and nature of events and processes in becoming a woman entrepreneur within a particular context. Models should recognize the diversity of development that reflects the different situations of women entrepreneurs. Transitions through various stages require the development of appropriate skills and abilities, and a desire to meet the demands of new roles in successive stages. Progression also depends upon accessibility to suitable opportunities. An understanding of entrepreneurial careers and processes and the experiences of women entrepreneurs in Zimbabwe will contribute to a better understanding of entrepreneurship, especially within the African context. A lack of knowledge of women entrepreneurs in small and medium enterprises could result in policies and programs for education and training, micro-credit and financing, allocation of resources, and aid that do not meet the needs of women entrepreneurs.

It is important to note that most enterprises operated by women in Zimbabwe are small- and medium-scale and women constitute the vast majority in this sector. The benefits and importance of skills and technology in economic development and in the raising of living standards of the nation has long been recognized. Government and private agencies have indicated great interest in human resource development and training programs. Upon independence, the Government of Zimbabwe assumed responsibility for apprenticeship and training skilled workers, expanded its technical training base through the establishment and expansion of polytechnic and technical colleges and universities, and promoted free enterprise in facilitating and collaborating with private institutions in training the workforce. However, in the process of renewing and reaffirming the importance of skill acquisition by the public and private sectors, skill development among girls and women has been neglected ( Butler & Brown, 1993 ). This oversight has contributed to voids in knowledge and understanding of the processes, constraints, and consequences of construction and acquisition of skill and work by women entrepreneurs operating small and medium enterprises.

Assessing women entrepreneurs' work will help determine the skills, vocational training, and education they need. Steinberg (1990) claimed that the treatment of skilled work as the outcome of the labor market and political struggles, or as an objectively measurable set of mental and political job characteristics, has been greatly influenced by conventional conceptions of male-dominated managerial, professional, and craft work. She further points out that the term skill is gendered and perceived by women to include those skills that are validated by formal training and certification, which many women small and medium enterprises (WSMEs) entrepreneurs do not have.

In this study, the concept of skill was approached from a social rather than technical perspective. Therefore, it ceases to appear as a tangible entity, a capacity for work that some people have and others do not have ( Jackson, 1991 ). How individuals construct and perceive skill becomes an important determinant of the capabilities and abilities they believe they have to perform certain tasks and jobs. Furthermore, "skill" is a concept that serves to differentiate between different kinds of work and workers and to organize the relations among them. Jackson noted that it has been used to protect the interests of those who have power. It has come to express the interweaving of the technical organization of work with hierarchies of power and privilege between men and women, blacks and whites, and old and young. Skill designations are deeply implicated in the gender equity struggles.

Literature Review

Historical Perspective of Women and

Entrepreneurship in ZimbabweThe subordination of women in Zimbabwe had strong historical roots that were reinforced by contemporary legal codes, raising controversies and questions about historical continuity of the colonial and post-colonial states. Sylvester (1991) cited the example of whether all Zimbabweans came from distant lands or simply emigrated from neighboring countries. She pointed out that economic policies and political decisions that the Zimbabwean government adopted raised questions about whether the new Zimbabwean state is really new or an extension of the Rhodesian state, following a development path that diverges from or simply builds on the political economy of Rhodesia. Jolly (1994) noted that the relation between the colonial and the post-colonial codes of engendered ethnicity was not just one of discontinuity or continuity. There were questions of reconstructions or rearrangement of meaning in post-colonial situations, of terminologies that had prevailed in colonial contexts.

Colonization in Zimbabwe brought with it new social and economic forces on the indigenous population. Jolly (1994) contended that in southern Africa, the relations between colonizer and colonized were often inscribed through women's bodies. Missionaries and colonial administrators judged women as primarily responsible for the perceived depravity of African society ( Schmidt, 1991 ). Colonial forces including Christianity and capitalism, together with traditional patriarchal structures collaborated to control the behavior of women. Subjugation of women was used as a general strategy to maintain control over indigenous African people and resources ( Van Hook, 1994 ). In most cases, there was no conflict between the traditional and colonial systems as they were separate but supportive of one another within the national economy ( Imani Development, 1996 ). African men were able to reassert their authority over women while the colonialists by controlling African women were able to obtain cheap male labor ( Schmidt, 1991) . These forces and structures worked in tandem to restrain the advancement of Africans with severe consequences for women; for instance, where convenient, colonial policy makers were willing to uphold traditional gender relations. One such instance was the creation of "customary law." Customary law was developed by the colonial administrators in consultation with traditional "legal experts" of chiefs, headmen, and elders, all of whom were men as a mechanism of controlling and subordinating women. While custom had been both flexible and sensitive to extenuating circumstances, customary law was not ( Schmidt, 1991 ).

Colonial administrators designed policies that treated women as either dependents or mothers. They had different educational programs for girls and boys to impose their vision of women's proper role on Zimbabwean society. Girls and women were discriminated against by the colonial state's education policy in terms of access to and equity within the school system. The formal and hidden curricula were biased in favor of boys, preparing girls for domesticity and boys for work outside the home ( Gordon, 1996 ). Western ideals of women as homemakers dominated curricula and the important role women traditionally played in agriculture were ignored ( Seidman, 1984 ). The few African women who managed to complete their education with the necessary qualifications for entry into the modern economy faced further discrimination by race and gender in the work place. This was reflected in their wages, employment rates, and the types of jobs they held. African women were employed mainly in the public sector as nurses and teachers in institutions catering to Africans. They earned less than men because of the dubious breadwinner concept. Upon marriage, women were given temporary staff status and required to resign from their jobs to have children and reapply after delivery with no entitlements. In fact, they had to start at the bottom of the pay scale. Women's incomes were heavily taxed, since they were considered supplemental to their husbands' incomes.

The traditional background, which most aspiring entrepreneurs represented, hindered their ability to become entrepreneurs. The social and economic structures in traditional African society were based on a higher degree of collective responsibility and communal ownership of natural resources as compared with colonial structures ( Imani Development, 1996 ). Advancement of individuals within the various traditional social settings depended mostly on a set pattern of responsibilities and privileges that came with each person's maturity. An individual desiring to advance outside those lines had a more difficult time. Although there were exceptions to the norm, it would be a risk, as these individuals would be perceived as a threat to traditional authority.

As a result of colonial and traditional pressures, entrepreneurship was generally not encouraged. However, a few black businessmen owned small retail stores in African townships. Various laws were used to restrict and prohibit enterprise development among the indigenous population that resulted in legal entrenchment of racial exclusion ( Imani Development, 1996 ). The colonial government deliberately discouraged and marginalized the development of indigenous enterprises. Entrepreneurship among the African indigenous population has become a post-colonial phenomenon, especially among women.

Economic Development in Post-colonial Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe attained its independence in 1980. Seidman (1984) noted that the position of women in post-colonial Zimbabwe was the result of complex interactions among three distinct legacies. These included the traditional patriarchal culture which subordinated women, colonialism which entrenched the inequalities of the sexual division of labor, and the experience of the war of liberation which created new aspirations for women in Zimbabwe. Men and women had high expectations of enjoying the fruits of independence. For women, this implied improvement in their social, economic, legal, and political status. During the liberation struggle, black Zimbabwean women had described their goals in terms of freedom from racial, economic, and gender oppression ( Seidman, 1984 ).

Although the government of Zimbabwe assumed the task of removing the distinct legal injustices, societal attitudes, and resistance to change, the majority of women continue to live under the same conditions that existed before independence. Therefore, their lives have not changed, in spite of the many legal changes that have occurred since independence. Another objective of the government was to bring all citizens into the mainstream of development and social transformation. This would ensure equality, regardless of race, color, creed, political affiliation, or sex. However, some articles in the Bill of Rights of the Zimbabwean Constitution refer to individuals and do not mention gender, and this has constituted the major barriers in realizing the transformation.

Although the economy of Zimbabwe has experienced an average growth rate of approximately 4% since 1980, in the 1990's, and 2000's, the growth rate decreased, in part, because of excessive government expenditure compounded by inappropriate and ill-conceived economic liberalization policies, and severe droughts in 1992, 1995, and 2002. Under pressure from the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, the Zimbabwe government adopted economic reforms. Ghosh (1996) defined economic liberalization as economic and industrial restructuring along the lines of capitalism in which private ownership, profit making, and a market framework regulated activity. In many developing countries, they have taken the form of neo-liberal packages of adjustment measures associated with financial support from the IMF and the World Bank. The current economic strategies attempt to combine stabilization and structural adjustment under an umbrella of liberalization. However, economic structural adjustment has not been very successful and its impact has not been uniform. Evidence suggested that women have been the most susceptible to the adverse effects of these policies ( Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 1994 ).

Zimbabwe has its own history, which negatively impacted on the development and participation of women in the informal sector. The system of economic controls established before independence provided white Zimbabwean firms with monopolies and other privileges to control markets for the most profitable products. Many of these controls remain in place. In Zimbabwe, as in South Africa, laws that prohibited Africans from operating certain businesses remained until the 1990s, resulting in an underdeveloped informal sector ( McPherson, 1996 ). The drastic impact these factors have had on women is demonstrated by a World Bank survey of women entrepreneurs in Zimbabwe. Only 5 percent of the respondents had obtained formal credit, while 75 percent of the respondents received financing from personal savings or family grants and loans ( Downing, 1995 ). However, the Growth and Equity through Microenterprise Investments and Institutions (GEMINI) data for Southern Africa indicated that women (84 % in Swaziland, 73 % in Lesotho, 62% in South Africa, and 67 % in Zimbabwe) own most of the SMEs ( McPherson, 1998 ). The gender data suggest the important role of women within the SMEs.

Further analysis of the sub-sector indicates a dominance of women in retail trade. However, the growth rate of enterprises owned by men surpasses that of women. The GEMINI Southern Africa data suggest that women have more barriers than men in the development of their SMEs ( McPherson, 1996 ). For example, it was revealed that employment growth rates for women's enterprises were generally lower than those for men's, and, remained the same size regardless of location along the urban-rural continuum. Frequently cited problems for women entrepreneurs included under-capitalization and inadequate market demand.

Women Entrepreneurs in Developing Countries

The decision to engage in WSMEs is an important one for many African women. A number of factors and issues promote or constrain their participation Environmental, cultural, and other socio-economic factors are important considerations in studying women's small and medium enterprise participation and activities. For example, the entrepreneurial activities of fresh produce market women in Harare, Zimbabwe evolved from historical circumstances, cultural work ethics, and individual resiliency ( Horn, 1994 ). They developed a marketing niche based on their ability to adapt rurally generated skills to an urban environment.

The ability of women to further develop their enterprises requires official government recognition of their integral role in the maintenance of their families, education of the next generation, and development of the urban community ( Dignard & Havet, 1995 ). Development will be highly problematic if the economic structural adjustment program or similar policies continue to undermine women's entrepreneurial activities. It is also equally important to recognize other WSMEs and not aggregate them in the same category as market women, as the needs of each group are distinctly different. Women in Zimbabwe were engaged in entrepreneurial small- and medium-scale capitalist ventures, typically in productive sectors such as light manufacturing. Since independence women entrepreneurs have shifted from manufacturing related operations into trading and, to a smaller extent, serviceoriented firms. Table 1 shows the industrial sector distribution of small and medium enterprises in Zimbabwe.

Table 1

Sector Distribution of Small and Medium Enterprises in Zimbabwe

Distribution of Sector % SMEs WSMEs (%)

Manufacturing 42.4 47 Food and beverages 5.3 2.8 Textiles 20.1 33.9 Wood and wood products 9.4 6.6 Paper, printing, and publishing 0.1 0.0 Chemicals and plastics 0.4 0.3 Non-metallic mineral processing 1.3 0.7 Fabricated metal 2.6 0.1 Other manufacturing 3.3 2.6 Construction 1.0 0.1 Trade 45.2 47.3 Wholesale trade 0.1 0.1 Retail trade 44.6 47.1 Restaurants, hotels, bars 0.6 0.2 Transport 0.6 0.1 Renting rooms and flats 6.8 2.3 Services 4.0 3.2

All sectors 100% 100%

Note. Source: McPherson, 1998 .

While women occupy a dominant position in the SMEs sector, in Zimbabwe they face particular problems. Women entrepreneurs are discriminated against when seeking loans and other support. Many regulations and controls on markets for raw materials, technology imports, and zoning by-laws target female-dominated sectors such as textiles, food processing, leather works, and retail sub-sectors. According to the Zimbabwe Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning, female self-employment in Zimbabwe experienced five times the growth rate of male self-employment in 1995. While the total of women-owned businesses has fallen 3.8% since 1991, one or more women currently owned 58% of the enterprises. Women owned nearly 75% of the SMEs in 1998 ( McPherson, 1998 ).

Entrepreneurial Career and Skill Development

To understand how WSMEs emerge, grow, and remain a vibrant and dynamic sector of the economy it is important to investigate women's entrepreneurial career and skill development. In addition, the strategies women develop for occupying this sector need to be understood in developing policies to support them. Life history approaches can assist to better understand women's entrepreneurial careers ( Scheibel, 1999 ). These acknowledge the role played by various factors in a woman entrepreneur's life. Since entrepreneurship is a capitalist venture through which an individual accumulates capital, examining the strategies a woman entrepreneur has used to develop her capital base provides insight into entrepreneurial career development. A wide range of factors, many of them deeply embedded in the gendered nature of culture and society, serve to prevent women from participating equally with men in education and training and; thereafter, in employment and selfemployment ( Leach, 1996 ). In general, formal education and training in developing countries appear not to acknowledge the involvement of women in economic activities, and does little to provide them with relevant skills. The gendered nature of the curriculum serves to reinforce rather than weaken the social and economic constraints operating against the equal participation of women in the labor market, which is both highly competitive and discriminatory.

Although a sound general education provides young people with the best foundation for their future participation in employment or entrepreneurship, additional training and skill development is necessary for a successful career as an entrepreneur ( Leach, 1996 ). Traditional apprenticeship has been the main mode of transmission of skills from generation to generation and is pervasive throughout many small and medium enterprises in Africa. However, there still is a need for improvement and intervention. McLaughlin (1989) identified three reasons to justify interventions in training: (a) inadequate capacity, (b) inadequate acquisition of knowledge or skill by trainees, and (c) the perception that conventional modes of skill acquisition do not satisfy the needs of entrepreneurship. Literature has indicated that training for women entrepreneurs in Africa remains very limited. Its emergence, in part, is a result of the recognition that SMEs have potential for sustainable economic development.

Vocational opportunities for girls, when available, have been restricted to careers traditional to women such as home economics, secretarial studies, dressmaking, and cosmetology, which are largely an extension of home-based activities and usually have low remuneration ( Leach, 1996 ). Therefore, the function of education has been largely to prepare young women for their assumed adult roles as housewives and mothers. In contrast, boys have been prepared for higher paying technical jobs and careers. Schools have served to reflect and to reinforce the gender bias that prevails throughout the labor market as in all social relations. Likewise, initiatives to introduce entrepreneurship into the school curriculum are unlikely to assist women significantly unless the needs of women are taken into consideration in the design and development of such curricula, and deliberate efforts in equalizing opportunity for men and women are made by policy makers ( Leach, 1996 ).

It is clear that career development pathways are very ambiguous. It becomes necessary to seek alternative conceptualization of women's entrepreneurial careers. Entrepreneurial career development could be theorized from Bourdieu's (1986) perspective of forms of capital. Entrepreneurial career development can also be viewed as an acquisition of various forms of capital. The forms and the extent of the accumulation reveal varying career patterns among entrepreneurs. The concept of capital as presented by Bourdieu is broader than the monetary definition of capital, more often used in economics. Capital is a generalized "resource" that can assume monetary and non-monetary, as well as tangible and intangible forms ( Anheier, Gerhards, & Romo, 1995 ). The social world is amassed history and, therefore, it is necessary to consider the idea of capital and all its effects.

"Capital is accumulated labor in its materialized form or its "incorporated" embodied form. … [it] takes time to accumulate and has a potential capacity to produce profits and reproduce itself in identical or expanded forms" ( Bourdieu, 1986 , p241).

Depending on the area in which it functions, and the cost of the expensive transformations which are the precondition for its usefulness, capital exists in economic, cultural, and social forms. Economic capital refers to income and other financial resources and assets. It is defined as that which is "immediately and directly convertible into money and may be institutionalized in the form of property rights" ( Bourdieu, 1986 , p243). Less tangible than economic capital, cultural capital can be invested and earn profit or increase in value ( Dinello, 1998 ). Cultural capital includes long-standing dispositions and habits acquired through the socialization process, and the accumulation of valued cultural objects such as formal educational qualifications and training ( Bourdieu, 1986 ; Coleman, 1988 ). Cultural capital defines and legitimizes cultural, moral, and artistic values; standards; and styles ( Dinello, 1998 ).

Social capital refers to social relationships that form resources that individuals can use in their personal and professional lives. It is comparable to the financial and human capital relationships of economics and a linkage to social structure ( Hofferth, Boisjoly, Duncan, 1999 ). Social capital is the actual and potential resources that can be accumulated thorough membership in social networks of individuals and organizations ( Anheier, Gerhards, & Romo, 1995 ). It is defined in terms of resources that individuals may access through social ties ( Frank & Yasumoto, 1998 ). These ties may affect one individual's action that is directed toward another based on the social structure in which the actions are embedded and the history of transactions between people. Social capital can also be described as the resources of social relations and networks that are useful for individuals. It facilitates action through the generation of trust; the establishment of obligations, expectations, and reciprocity; and the creation and enforcement of norms and sanctions ( Coleman, 1988 , 1990 ; Putnam, 1995 ). It also refers to the ability to form and sustain associations ( Portes, & Landolt, 1996 ). Further, social capital has other distinctive characteristics including the expectation of reciprocity that distinguishes it from economic capital. These characteristics of social capital may impose restrictions on individual freedom and business initiatives. Close social networks can also undermine business initiatives through downward leveling pressures.

Economic, social, and cultural capital can be converted one into another. However, they differ in liquidity and convertibility and in their potential for loss through attrition and inflation. Economic capital is the most liquid and readily convertible into social and cultural capital ( Anheier, Gerhards, & Romo, 1995 ). By comparison, the convertibility of social capital into economic capital is more expensive and conditional. Social capital is less liquid, "stickier," and less likely to lose value. While it is more difficult to convert social into cultural capital, the conversion of cultural into social capital is easier.

The differences in the liquidity, convertibility, and loss potential of capital entail different scenarios for persons in social fields. Bourdieu (1986) further noted that high volumes of economic capital with lower volumes of cultural and social capital characterize some positions. Other positions will rank high in terms of cultural capital, yet somewhat lower in other forms. The "nouveaux rich," for example, are typically well endowed with economic capital relative to a paucity of cultural capital. International business consultants rely on high levels of social capital relative to cultural and economic capital. In contrast, intellectuals typically accumulate larger amounts of cultural and symbolic capital than they do economic and social endowments. The entrepreneurial careers of women appear to require a balance in the different forms of capital. Economic capital provides the base required to create a new venture. However, access to economic capital is facilitated by the social capital an individual possesses. Cultural capital in the forms of class, educational background, and ethnicity can provide contacts with certain members of society; thereby, contributing to the social capital of the woman entrepreneur.

Methodology

Theoretical Framework: Hermeneutic Phenomenology

Phenomenology is the study of human phenomena and focuses on the "lived experience"; whereas; hermeneutics refers to the interpretation of the experience ( Wilson & Hutchinson, 1991 ). According to Van Manen (1990) , phenomenological research is the explanation of phenomena as we become aware of them. In seeking to determine, "Who is a woman entrepreneur in Zimbabwe?" the study examined and described the experiences of women entrepreneurs in Zimbabwe and their interpretation of the world, situating them in the colonial and post-colonial state. It focused on the questions, "What is the structure and essence of experience of the entrepreneurial phenomenon for these women?" and "What experiences have these women had and how do they interpret the world around them?"

It was the intention of the researcher to attempt to examine the experience of becoming an entrepreneur in Zimbabwe while gaining a deeper understanding of the nature or meaning of the everyday experiences of entrepreneurial women. Also, the study intended to contextualize phenomena and allow for the exploration of the experiences of participants from their own perspectives and words ( Richie, Fassinger, Linn, Johnson, Prosser, & Robinson, 1997 ). From a phenomenological perspective, it was important to realize that there was no objective or separate reality; there was only what the women knew based on their experiences and what these experiences signified to them.

Phenomenology has played a critical role in establishing and detailing the complexities of human experience ( Maranhão, 1986 ). The assumption in phenomenology is that there is an essence(s) to shared experiences, which represent the core meanings mutually understood through a phenomenon of common experiences and that the phenomenon by itself has no inherent meaning. The experiences of people are categorized and compared to identify the essences of the phenomenon. Phenomenology is the systematic attempt to uncover and describe the structures and the internal meaning structures of the lived experience ( Patton, 1990 ). It focuses on the shared world of meanings through which social action is generated and interpreted. The phenomenon is represented by the interpretations of members of a society. All situations have meanings, and are revealed and related to other meanings and meaning systems ( Jain, 1985 ).

The purpose of hermeneutics is to discover meaning and achieve understanding rather than extracting theoretical terms or concepts at a higher level of abstraction ( Wilson & Hutchinson, 1991 ). Hermeneutic phenomenology, therefore, becomes an interpretation of people's text of their experiences. Hermeneutics emphasizes the human experiences of understanding and interpretation and is presented as an individual's detailed stories or "thick description." These serve as exemplars and paradigm cases of everyday practices and "lived experiences." The practices and experiences are identified, described, and interpreted within their given contexts.

"The aim is to understand how people experience the world pre-reflectively, without taxonomizing, classifying or abstracting it." ( Van Manen, 1990 p.9).

Hermeneutic phenomenological research informs the personal insight, contributing to thoughtfulness, and the ability to act toward others, children or adults, with tact or tactfulness ( Van Manen, 1990 ). Hermeneutical phenomenology attempts to construct a full interpretive description of some aspect of the world, with a full understanding that the lived life is always more complex than any explanation of meaning can reveal. The focus is on interpretation and understanding social interactions and those experiences that influence the development of the individual's life. Life-course perspectives used in phenomenology and hermeneutics emphasize how women's attitudes, orientations, and commitments to entrepreneurship are constantly renegotiated and not fixed over time ( Scheibel, 1999 ).

A methodological commitment to the specific cultural and historical processes grounded in the activities and practices of women highlights the importance of social agency and resistance ( Lal, 1995 ). The concept of agency, which articulates women's freedom to respond to social constraints proactively, has been absent from many discussions in the study of women's entrepreneurial careers ( Scheibel, 1999 ). In discussing women's agency, the emphasis is placed on the creative mechanisms employed differentially by women entrepreneurs to ensure the development of their careers. It also expresses women's capacity to devise strategies for expressing their autonomy and satisfying some of their interests. The concept of structure is also required to uncover the reality of power inequalities and gender differences that are deeply embedded within organizational structures. This study did not seek to aggregate women's understandings, perceptions, and constructions of their careers into a single construct. It attempted to present the full range and variety of experiences ( Guba & Lincoln, 1994 ).

Feminist Theory

A feminist lens was used to focus on those salient features about gender relations and gender identity without reproducing patriarchal bias. This study sought to conceptualize the experiences of women entrepreneurs in Zimbabwe in the development of their careers from their standpoint. In seeking to understand the process of female entrepreneurship, it would have been inadequate to "add women" to the current understanding of entrepreneurship which fails to consider the realities of women's experiences in business, "and stir" ( Green & Cohen, 1995 ). A reformulation that considers the central tenet that women's lives are important was necessary. Accordingly, feminist standpoint epistemology was most appropriate.

Standpoint epistemologies have provided some of the most important challenges to the conventional view that true knowledge is objective, value-free, disinterested, and universal ( Pels, 1996 ). Standpoint epistemologies take women's experience as a starting point for feminist and sociological discourse ( New, 1998 ). Black feminist thought is comprised of ideas produced by black women that illuminate a standpoint of and for black women ( Hill-Collins, 1990 , 1991 ). Accordingly, three key assumptions underlie black feminist thought. First, while others may record black feminist thought, black women produce it. The second assumption is that black women have a unique standpoint that is different from other women. Third, universal themes included in black women's standpoint may be experienced and expressed differently as a result of diversity of class, region, age, and sexual orientation. By conveying new meaning to these core themes of black women's standpoint is extrapolated to African women. It is evident that African women's experiences with racial and gender oppression result in needs and problems quite distinct from white women, western women, and men. African women struggle for equality as women and as Africans.

Feminist standpoint epistemology as a lens was relevant to this study as it recognized the fact that women are diverse and socially positioned in other areas that affect their lives. Consequently, their ways of understanding their own situations and perspectives of the world are diverse ( New, 1998 ). It is important to consider women's experiences as a beginning to gain knowledge of these understandings and perspectives. Feminist standpoint epistemology is a method of speaking that is not appropriated by the discourses of those in power ( New, 1998 ).

Standpoint texts are organized in terms of several assumptions ( Denzin, 1997 ). The starting point was the experiences of persons including women, persons of color, post-colonial writers, gays, lesbians, and others who had been excluded from the dominant discourses in the human disciplines. The experiences of African women entrepreneurs in post-colonial Zimbabwe were in the focus of this study. Standpoint epistemologies question the standpoint from which traditional, patriarchal social science had been constructed. Secondly, in standpoint epistemology, the categories that classify people are necessarily non-essentializing. Standpoint epistemologies attempt to discover new knowledge regarding how the world works in the lives of oppressed people. It also intends to recover and derive value to knowledge that has been suppressed by existing epistemologies. Denzin further noted that feminist standpoint epistemology begins with the subject who knows the "world directly through experience." The argument is that experience as the starting point for social change has the potential for empowerment.

This study sought to address the richness and complexities of entrepreneurship as part of a woman's life. In addition, the study also sought to give voice, make visible, place at the center, and challenge entrepreneurial career development models that are directly or indirectly influenced by dominant constructions of gender ( Avis & Nickerson, 1996 ). A feminist lens allowed the examination of the ways in which the colonial and post-colonial state impacted the development of women's entrepreneurial careers. From this perspective, the state ceases to be a neutral overseer of national affairs. Its actions are examined to determine complicity in the subordination of women through legislation and policies.

Williams (1991) contended that there was a tendency to decontextualize the subject matter by making categorical statements about men and women that obscure the experience of gender by different social groups and in various contexts. The criticism of western feminism focuses on the need to understand African women's problems and issues from their perspective rather than adding ethnocentric biases derived from the experiences of non-African women and their cultures ( Gordon, 1996 ). In addition, there is a need to recognize the diverse ways African women perceive and deal with women's issues. Further, there is a need to incorporate these ways into the development programs and other reforms designed to help African women; rather than impose western strategies and solutions that are insensitive to cultural beliefs and practices.

Research Design

This study was designed to understand and explain the processes and mechanisms of the entrepreneurial career development of women in Zimbabwe from individual and institutional perspectives. It was intended to examine how layers of recurring themes and relationships among the various aspects of the careers of women entrepreneurs in Zimbabwe were manifested using naturalistic methods. The naturalistic inquirer operates under a set of assumptions different from the positivist inquirer concerning the nature of reality, epistemology, and generalizability ( Lincoln & Guba, 1985 ). The intent is to develop shared constructions that illuminate a particular context and provide working hypotheses for the investigation of others ( Erlandson, Harris, Skipper, & Allen, 1993 ).

To illuminate the intricate and complex nature of women entrepreneurship, a multi-method research design incorporating interviews, observations, and case studies was used. The use of multiple methods or triangulation was an attempt to secure an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon in question ( Fine, M., Weis, L., Wessen, S. & Wong, L., 2000 ). It is impossible to capture objective reality in any study, especially in a qualitative study. The combination of multiple methods, empirical documents, perspectives, and observations in a single study was a strategy that added rigor, breadth, and depth to the investigation ( Fine, M., Weis, L., Wessen, S. & Wong, L., 2000 ). Case studies were used to collect data as the phenomenon under study was closely related to the context ( Yin, 1993 ). Further, inclusion of context created a richness such that the study could not rely on a single data set. Case study as a method is especially suited to capturing the phenomenon of "experiential descriptions," by studying the uniqueness of the particular, an understanding of the universal is developed ( Elliot, 1990 ; Simons, 1996 ). Elliot (1990) described this phenomenon as the paradox of the case study.

Research Questions

The following research questions regarding women entrepreneurs in small and medium enterprises in Zimbabwe were posited:

- Who is a woman entrepreneur in Zimbabwe?

- What are the mechanisms and processes experienced by, and resources available to, women in developing entrepreneurial careers?

- What is the role of the colonial and post-colonial states in Zimbabwe in the development of women entrepreneurs in Zimbabwe?

Data Sources

The identification and selection of participants was a difficult task because entrepreneurs were completely self-managed. Since many women entrepreneurs were not accountable to any particular organization or authority, obtaining their consent for interviews was not easy. At this stage, the purpose was to conduct as many interviews as possible to allow a representative selection of participants for case study. During this phase, various government, non-government, and private establishments that impacted the development of entrepreneurial careers were visited. Women were selected based on uniqueness of enterprise, educational background, turnover, and willingness to participate in the study. This allowed for a cross-section of the various enterprises.

Setting and Selection of Participants

The site of this study was urban Zimbabwe, located in the two largest cities of Harare and Bulawayo. Zimbabwe, a former British colony is located in southern Africa. It shares boarders with South Africa to the south, Mozambique to the east, Zambia to the north, and Botswana to the southwest. It is completely landlocked

Purposive sampling was used to identify and choose participants for the study. Purposive sampling permitted a selection of informants that would provide rich detail of the phenomenon. The sampling procedure deliberately sought both the typical and the divergent data that the emergent insights suggested was relevant to the study. Purposive and directed sampling through human instrumentation increased the range of data and maximized the researcher's ability to identify emerging themes that adequately accounted for contextual conditions and cultural norms ( Erlandson, Harris, Skipper, & Allen, 1993 ). Three participants were selected for detailed case studies. Participants were studied in their natural settings enabling the researcher to ground observations and concepts. Career and life histories were obtained during unstructured interviews. Women entrepreneurs were asked to explain their primary and secondary reasons or motivations for entering business.

Data Collection

The interviews explored the perceptions of the women about their work; their skills, families, social and business networks; and identified barriers they had encountered in their entrepreneurial carriers and plans for the future. Each interview was uniquely different. No attempt was made to maintain any position of privilege. There was no need to attempt power sharing; subjects were made to feel like they held all the power. They could choose to speak, not to answer some questions, and terminate the interview at any point. Burgess-Limerick (1993) noted that the relationship between interviewer and interviewee creates a unique bond. Interviewing the subjects allowed for the exploration of a range of emotions, which were not always possible to predict.

Data Analysis

The data obtained developed a solid basis for identifying patterns, themes, and concepts ( Miles & Huberman, 1994 ). An inclusive approach to the cases was used as the study sought to capture women entrepreneurs as they experienced their natural, everyday circumstances and offered the researcher understandings in larger social contexts of actors, actions, and motives. The case studies were analyzed initially using case analysis. Case analysis entailed organizing the data by specific cases for in-depth study. This involved immersion in the cases and thorough reading. After immersion in the data, each case was organized. After the case data had been accumulated from the interviews, observations, and documents, case records were compiled by narration.

Case records were compared with each other using cross-case analysis. Crosscase analysis expanded understanding and explanation. Various interpretations within and across cases were compared and contrasted. This entailed comparing themes, metaphors, and explanatory stories across cases. Comparing interpretations led to new insights into the cases. Common patterns across cases coalesced into a grounded theory of the subject ( Rossman, 1993 ). The use of cross-case analysis enhanced the description of data to generate theory by extending beyond just one specific case.

Themes were at a conceptual level of analysis and evolved from systematic reflection on and interpretation of narrative data ( Wilson & Hutchinson, 1991 ). Patterns and themes common to the cases of the women entrepreneurs were allowed to emerge from the categories developed. The challenge was to develop interpretations sufficiently general and comparable to the other cases, yet grounded in the details of the specific case. Locating themes that transcended cases through the use of inductive coding permitted the identification of recurring themes. The constant comparative method ( Glaser & Strauss, 1967 ) allowed for the inductive search of emergent patterns, convergences, and divergences in the cases which was guided by the research questions, and conceptual framework ( Patton, 1990 ).

Findings

Case studies were conducted and detailed accounts of the entrepreneurial careers of three women in Zimbabwe were obtained to answer research questions 1 and 2. Field notes, audiotapes, and other secondary sources including newspapers and magazine articles were used to obtain an understanding of the woman entrepreneur. The accounts of three participants followed a general pattern of a vision in venture creation. The impetus for developing vision was derived either from negative experiences such as being laid off, or positive experiences such as promotion that inspired and motivated self-employment.

Case Study 1: Angela - Interior Design Company

Angela owned Interior Design Company (IDC). The company was operated as a loose partnership with a sister-in-law. The main activities of the company were soft furnishings, carpeting, tiling, and upholstering. The company also dealt with upholstery, furniture supply, and exclusive garment making. The IDC was the first and only distributor of pinch pleat drapery in Zimbabwe and the second manufacturer of pinch-pleated drapes in Southern Africa. Major markets for the company were homes, corporate offices, and hotels. The main processes at the company factory, located in downtown Harare, were design, cutting, and sewing.

The company had a range of machinery, but the production system was not automatic. There were no automated production machines. The company had some computers for accounting and other activities. It had a retail outlet on the same premises as the factory. The company made and sold soft furnishings and ethnic African women's clothing. The company had high-tech equipment with excellent labor relations. The administrative manager rated the products average since some products had previously been returned for poor workmanship. She also considered their product inspection methods as average. In terms of profitability and working capital, she considered them above average. The company stated as a major problem was collection of debt.

Born and raised in an African township in Harare, Angela had impressive academic achievements. She held a B.A. degree from a university in the United Kingdom and a M.A. degree from Sweden. She was now studying for a Ph.D. in enterprise development. The experience she gained in transforming her company from a backyard business into a successful enterprise, despite the numerous obstacles, had been helpful in dealing with the problems and challenges. The IDC had 18 employees and was recognized as one of the country's top emerging industries. Angela had been successful, in part, because of perseverance and her ability to analyze a situation or problem and transform it into a business opportunity. "I look at every problem with a different eye from others. Where some people see a hurdle, I see a business opportunity. I find a way of turning a situation into a business opportunity … I have done that on many occasions," she said.

Through hard work and ingenuity, Angela was able to establish her interior design and décor firm. The company she started as a cottage industry in 1991 had grown into a fully fledged business with an impressive clientele. It had taken a lot of patience and perseverance for her to get where she was today. As a mother of four, she had to make many sacrifices. Angela considered herself aggressive with a vision. She was innovative and had the ability to transform obstacles or problems into business opportunities. Angela became Africa's first certified window fashions professional. The Window Fashions Certified Professional designation indicated to her customers and industry peers that she was a professional, committed to the highest levels of accomplishment and knowledge in the window treatment industry. The IDC was also highly rated internationally. She was able to expand her company very rapidly. "The challenge for us now is putting in new systems since the business is growing," she asserted ( Ncube, 1997 ).

Case Study 2: Evelyn-Women Building Contractors

Zimbabwean women were increasingly entering into business sectors formerly regarded as male domains. But as many will note, it was not easy, as determination and the will to succeed were vital. Evelyn fought great odds, venturing into the construction industry. Evelyn, who owned a construction company in Harare's neighboring city of Chitungwiza, admitted that it was not all-smooth sailing. She encountered a number of problems, which included delays in registering her company with the Zimbabwe Building Contractors' Association. The association was skeptical of a woman seeking to assert herself in the construction business. However, when her company was finally registered, she met a lot of resistance in the competitive male-dominated industry where it was the survival of the fittest.

The former volunteer worker owned Women Building Contractors (WBC). Despite numerous problems encountered during the initial stages of establishing the company, WBC was well established and competed with major contractors for tenders. Some of the successful construction projects were 20 houses in a highdensity suburb of Harare and a contract with an insurance company, which experienced the construction of several houses in low-density suburbs. The company also successfully completed another project of 50 houses in another high-density suburb in Harare.

In the early 1980's, Evelyn had worked as a volunteer with the Boy Scouts in the Chitungwiza schools. In 1983, she was among the volunteers chosen by the Swedish Scouts Association to receive training as bricklayers. They were trained onthe- job building Blair toilets (brick pit-latrines) in Epworth, a high-density suburb near Harare. Upon completion of the three-year project, she was certified as a bricklayer. Once the project was over, she found it was very difficult to find formal employment. "As a woman, it was difficult to secure formal employment and I began doing 'self-help jobs' on a small scale in the suburb," she said. With a few jobs to her credit, she was able to secure employment in the then Ministry of Public Construction and National Housing as a bricklayer and worked there for six years before being retrenched.

By the time Evelyn was retrenched, she had already carried out a market survey and had started making plans to venture into private business. Her employment severance package was not enough to procure the needed equipment so she sought financial assistance, a futile exercise. "I got no joy from financial institutions. The question that I was being asked suggested to me that the officers had no faith in me simply because I was a woman. I almost gave up had it not been the encouragement I got from my husband." Later, she approached the Social Dimensions Fund (a government social security fund) and obtained Z$80,000 which she used to buy basic equipment and to secure offices. With hard work and determination, her company flourished and employed 18 people including five women. Evelyn and her husband performed all the office work and trained staff.

Reflecting on 1992, Evelyn recalled the problems and resistance she encountered. She had proved that she could, indeed, compete in the construction industry. She remarked, "I feel I was not designed for anything other than building. I love my job because I understand it, and, mind you, building is not done by someone who needs a push from somebody [else]." Among major projects she had completed was the construction of several houses in Harare's suburbs of Budiriro, Msasa Park, Waterfalls, and Warren Park. She said that even today, men still do not believe a woman could own and operate a construction company. Some were not happy with her leadership position and threatened to quit after realizing she was in charge. Such attitudes did not bother her much since employees were quick to realize her capabilities.

Evelyn believed that the time had come for Zimbabwean women entrepreneurs to prove to the nation that they had an important role to play in the economic development of the country. She believed that nothing should be reserved for a particular gender because individuals had their own talents.

Case Study 3: Katherine - Kathy Products

Katherine was well known throughout Zimbabwe. She owned Kathy Products and manufactured cosmetic products. A tough hard-working woman, she was also known for helping to change the Zimbabwean people's attitudes toward women entrepreneurs. In the 1990's, she campaigned for the indigenization of businesses.

Katherine experienced all the frustrations of being discriminated against as a black woman through racism and patriarchal attitudes. The experience molded her into a very determined campaigner for women's rights. Her experience in business taught her that women could do as well or even better than their male counterparts if afforded the opportunity. Her inspiration to start her business came from the plight of black people yearning to have cosmetics appropriate for their skin type. Katherine then started manufacturing skin products from her backyard, unaware that her products would become a regional phenomenon ( Saburi, 1996 ). While living in Europe, she adjusted to the temperate climate, but upon returning to Zimbabwe in the late 1970's, she found the Southern African climate extremely dry and hot. All her cosmetics became unsuitable for the environment. As a model and actress, she chose not to gamble with cosmetics and developed an enterprising idea to make black cosmetics.

In 1978, Katherine opened a hairdressing salon at a local shopping center, using the small savings from her salary as a nurse and Z$2,000 borrowed from her father. A hairdressing salon was not enough to satisfy an ambitious woman with a keen interest in the small-scale manufacturing of cosmetics for African women. The popularity she had gained while featuring in movies and television in London led to her fame. During her three-year stint in the London film industry, Katherine had performed with world-renowned actors. Katherine began to experiment with the small-scale production of cosmetics for African women with the help of a pharmacist. At the time, she was operating from her Waterfalls (a suburb of Harare) home. During the same year, she diversified and opened a boutique in downtown, Harare. Unfortunately, this venture did not succeed. Katherine thought that she did not have the skills required to operate a boutique. She abandoned the venture and returned to black cosmetics. Working from her kitchen, it soon became too small to accommodate large orders placed by retailers. In 1980, she formed a joint venture with another woman, contributing Z$5000 each and a car to start a factory.

This marked the beginning of Kathy Products. The business did so well that in 1984, Katherine won the Businesswoman of the Year Award from a local chamber of commerce. In 1987, her partner withdrew from the joint venture. Her businesses employed 184 people specializing in hair and skin care. Exports gained acceptance in regional countries such as Tanzania, Malawi, Mozambique, and Zambia.

Joining the male-dominated business world was not easy for Katherine at the time since there was much debate regarding the role of women in society. She often confronted uncompromising attitudes from many men and sometimes women. People would close doors in her face just for being a woman in business. However, this did not deter her as each time the door was closed she knocked even louder. She fought patriarchal, traditional beliefs and misconceptions about women participating in the mainstream of the economy. Katherine maintained that much needed to be done to change people's attitudes. She suggested that the first step would be to begin by having parents educate their boys to respect girls and for girls to believe in themselves.

Katherine was a very hard-working woman and won recognition for her sterling efforts. A passionate fighter for women's rights, she was a pioneer of the Indigenous Business Women Organization and was elected secretary general of the organization. During the same year, she was appointed to a development corporation board. She was appointed as a trustee of a children's foundation. She had been a board member of other development organizations.

Katherine said she planned to open two more businesses outside Zimbabwe that would specialize in the production of cosmetics. In addition, she would use her strength and influence to mobilize and raise awareness among women who wanted to enter into business. Financial problems were also major issues facing women entrepreneurs. Katherine said she had survived by utilizing profits earned from her external operations to finance the Zimbabwean business.

Although she had managed to establish a large venture using her meager resources, she said the government should introduce incentives to encourage the formation of more businesses. Vast commitments in business had forced her to abandon modeling and acting, however, she remained involved in the film industry. She left a mark with her successful production of a Z$2,5 million feature film. She was married with two children. "I had all the support from my family." Katherine had now expanded her business to the south of Zimbabwe in Johannesburg, South Africa and Gaborone, Botswana.

Case Analyses

Categorization and Narrative Composition

Events considered as important in the entrepreneurial career development process were identified and summarized. Events were then categorized and used to clarify the chronology for each of the three cases. Accounts were compared with regard to how categories were ordered chronologically, their roles or significance of in the story, and the relationships of the categories with each other. In this way, different patterns or plots were identified ( Miles & Huberman, 1994 ). Categories were grouped into themes, a commonality that possesses both descriptive content and evaluative significance within a story, focusing on the events and outcomes. The analytic emphasis of categorization requires a complementary analysis, synthesis, and interrelation within a whole narrative ( Rossman, 1993 ).

Angela reported a number of incidents and events associated with the establishment and operation of her business. She met many challenges and problems which she was able to overcome through perseverance. She attributed success to her mother and family support.

Katherine's narrative revolved around the sense of challenging and placing herself in new and demanding situations. The narrative was one in which she transitioned from being a nurse to a self- employed hairdresser, to a backyard manufacturer, and finally to a full-scale cosmetic manufacturer.

Evelyn was a contrast with the other two women. Evelyn was not highly educated and chose an entrepreneurial career in a field non-traditional to women. Her business developed from being laid off and experiencing difficulty finding employment as a female builder. All the women had strong political connections. Participants manifested eight common themes in the development of their entrepreneurial careers (see Table 2).

Table 2

Case Analyses: Development of Themes of an Entrepreneurial Career

Themes and Categories Case 1: Angela Case 2: Evelyn Case 3: Katherine

1. Vision in Venture Creation Idea/Innovation

Pinch pleat drapes

Woman building

constructorAfro-cosmetics

Motivation Independence Retrenchment Independence Risk-taking New product

Non-traditional

careerNew product 2. Opportunity Initiative, exploration, Consult with experts market research Market research and information-

seekingand investigations

3. Self-concept Independence/Need for

powerAggressive

Self-motivated

Hard-working

Need for achievement Perseverance Dedication Determination Creativity Innovative Inspired Resourceful Gender consciousness Awareness of Belief in women's Women's right

women's issues

capabilities and

membership in

women's

organizationscampaigner and

membership in

women's

organizationsCoping ability,

frustration tolerance,

and stress managementAdaptability

Tolerance

Flexibility

4. Acquisition and Construction of Skill Managerial capability

Acquisition of

technologyDiverse workforce

Large workforce

Entrepreneurial spirit

Certified

professionalUse of acquired skill

Application of life

experiencesAnalytical ability

Perception of

opportunityMarket research prior

to business ventureDevelopment of

culturally appropriate

productCommunication skills College level Primary level College level Interpersonal skills

Excellent relations

with employeesAbility to retain male

employeesHigh employee

retention rateTechnical skills Constructed Acquired Constructed

5. Challenges and Adversity Capitalization Under-capitalized Under-capitalized Under-capitalized Source of start-up

capitalSavings

Savings and loan

Savings

Perception of Work-home mesh, Patriarchal attitudes Macro-economic difficulties

macro-economic

environment: ESAP

physical facilities

and technology

environment - ESAP,

patriarchal attitudes

6. Survival Technology acquisition

High tech

equipmentAppropriate

technologyHigh tech equipment

Resourcefulness/sense

of agencyProblem solving

skillsShowed initiative

Showed initiative

Division of Labor 18 employees 18 employees 184 employees

7. Networks Social Family and friends Family and friends Family and friends Business

Confederation of

Zimbabwean

Industries (CZI),

Zimbabwe National

Chamber of

Commerce (ZNCC),

BankBuilding

Construction

Association member

Secretary general-

Indigenous Business

Women Organisation

(IBWO), Million-

Dollar Round-Table,

CZI, ZNCC

Political

Ruling party

memberRuling party member

Ruling party member

8. Growth and Expansion Hopeful about the

futureAcquiring more

technologyExpanding

Continued expansion

Long-term planning Plans to build a

factorySecure bigger

government tendersExpand in sub-region

Recognition

Business Woman of

the Year, 1994,

1998. Newspaper

articlesNewspaper articles

Business Woman of

the Year, 1984,

Newspaper articles

Themes

1. Vision . The development of an entrepreneurial career started with an idea that was developed into a vision. The woman entrepreneur was able to see into the future what many others did not see, she had vision. The vision motivated her to create a new venture. Women mentioned that they always desired to own their own business, be independent, and earn more money.

Angela's vision was the introduction of pinch pleat into the Zimbabwean market. The IDC firm was the only factory in the country producing pinch-pleat drapes. Angela capitalized on an idea to start a business and capture a niche in the market. Evelyn ventured into the construction industry, and although this was a maledominated field, she envisioned possibilities for herself. Katherine entered cosmetics manufacturing with the vision of making products specifically targeted for black people.

2. Opportunity . Participants shaped circumstances in a favorable way or received the benefit of circumstances being shaped by others. For Angela, her opportunity emerged because she was able to obtain the required capital through the banks and donor aid. For Evelyn, the opportunity came when she was among Boy Scout leaders who were chosen to train as bricklayers overseas. Katherine had adequate savings to start a partnership with someone who had the knowledge and skills to manufacture cosmetics.

3. Self-Concept and Self-fulfillment . All women were very much aware of the patriarchal attitudes that prevailed in Zimbabwean culture. They had a strong need for independence and achievement. Angela described herself as aggressive. She had the vision to create a venture. She succeeded in the face of much adversity. She was adaptable and able to tolerate high levels of frustration. Evelyn was self- motivated and very dedicated to her work. Katherine was hard working and prevailed because of her determination. Her business was very successful and had expanded to the sub-region.

The experience of being an entrepreneur was voiced in terms of selffulfillment and agency, the capacity to respond to social constraints proactively. Angela who operated an interior design firm stated, "For me, there is no looking back. The sky is the limit and I am going to do everything within my means to ensure that my business grows and that we women take a greater active part in economic development." Independence, flexibility, and a sense of self are other ways in which they spoke about the impacts of their experiences in entrepreneurship. Evelyn identified with her occupation and said, "Generally women hesitate … some are not willing to put on overalls so it needs someone with a 'so-what' attitude. Dirt or no dirt, I love my job."

4. Acquisition and Construction of Skills . How individuals constructed and perceived skill became an important determinant of the abilities they believed that they possessed to perform certain tasks and jobs. Through attending training courses, volunteering, previous work experiences, and market research, participants engaged in various activities that allowed them not only to acquire skills but also to construct reality. Reality construction ranged from gaining an understanding of general economic conditions to learning about particular lines of work. In situations where women entrepreneurs had not acquired the required skills through training or previous experiences, they constructed these skills. Participants used skills acquired in previous experiences to construct new and required skills. For example, a woman entrepreneur may never have been in a managerial position, but to operate an enterprise, she required managerial skills. The entrepreneur, in such cases, would create a new repertoire of skills to accomplish the work.

Angela had B.A. and M.A. degrees and was currently working toward a Ph.D. From her educational background, she had accumulated skills and was able to transfer them to operating a business. Although Angela did not have the specific training and technological background in her chosen venture, she had a large enough repertoire of skills that gave her the confidence and belief that she would be able to successfully operate a soft furnishings venture using new technology. Evelyn, who only completed junior high school, compensated for her limited educational background by obtaining training as a bricklayer.

5. Challenges and Adversity . In the creation of a new venture, women entrepreneurs faced many challenges and much adversity in the forms of competitors, distracters, and patriarchal attitudes. Women entrepreneurs were confronted with all the growth problems that their male counterparts did and more including dealing with problems related to family, education, gender discrimination, lack of extensive networks. Sexton (1989) argued that all of these problems impacted on the women's personalities and their abilities to manage or expand their businesses. All of the women faced a lot of problems with under-capitalization. Banks would not initially approve loans to start their enterprises. They also encountered problems acquiring facilities. The macro-economic environment was deteriorating which made it very difficult for the women to profitably operate their businesses.

Angela had many problems early in establishing her venture. She had difficulty securing the necessary premises and capital. However, she persevered through determination and having the confidence that she would prevail. Evelyn had a difficult time breaking into the male-dominated field. She endured patriarchal attitudes that opposed and discouraged her from operating a building construction enterprise. Through resilience, she was able to survive. Katherine had also faced problems with patriarchal attitudes.

6. Survival . The survival of an enterprise depended on many factors. General ability was required for the successful operation of the business. Education and the skills acquired composed much of general ability. Specialized ability involved knowledge of a specific trade and leadership skills. Woman's agency, the ability to improvise and innovate in the face of adversity was a required characteristic of women entrepreneurs.

Creative ways of solving problems were required of women entrepreneurs to survive the challenges and adversity. They acquired the necessary technology and hired the required employees. They needed to have perseverance, determination, and resilience. Perseverance implied the will to continue in the enterprise in spite of obstacles, opposition, or discouragement. Determination was the resolve to prevail in the venture. Resilience was a set of attributes providing people with the strength and fortitude to confront overwhelming obstacles ( Sagor, 1996 ).

7. Networks . Personal networks consisted of all those persons with whom a woman entrepreneur had direct or indirect contacts. These included partners, suppliers, customers, bankers, creditors, distributors, association memberships, family members, and friends. Participants had personal networks that facilitated opportunities, resources, capitalization, and venture creation. People in their networks provided support in the forms of encouragement, advice, information, and approval.

Networks were an effective means of broadening the management skills and access to resources for women entrepreneurs. Aldrich (1989) noted that direct ties between an entrepreneur and contacts were important for the indirect access to resources they provided. Indirect ties enabled entrepreneurs to further increase their access to information and resources; thereby, enhancing what was available through their direct ties.

The personal networks of women entrepreneurs and their positions in larger social networks had a significant impact on women's access to information and advice, resources, and social support. It has been indicated that women generally inhabited a "female world" in which they deal mainly with other women on women's issues, generally in the private domain. This female world only partially overlapped the "male world" which was the public world of government, business, commerce, and other arenas. The extent and diversity of women's networks were limited in many important regions of social life by divisions and barriers ( Aldrich, 1989 ). Women lacked extensive networks.

Angela had a well-extended support network. She had her immediate and extended family support and operated the venture with a sister-in-law. In recognition of businesswomen's efforts, a local bank in Zimbabwe annually awarded the "Business Woman of the Year" trophy. Angela was awarded the prestigious "Business Woman of the Year" trophy twice. The First Lady of Zimbabwe also commissioned her enterprise in recognition of her business skills. In addition, Katherine won the coveted "Business Woman of the Year" trophy in 1984. Evelyn's personal network was well extended within the community she lived. She was a wellknown and respected woman. She had strong political, legal, and business connections.

8. Growth and Expansion . After their businesses were established and successful, women entrepreneurs developed long term plans to expand their businesses. Sexton (1989) noted that growth was neither good nor bad. It may be a measure of success to some but not to others. Lack of growth should not be viewed as failure, especially when applied to women-owned businesses. Growth should be viewed as the result of a choice made by the entrepreneur.

Women entrepreneurs in Zimbabwe were severely limited by the effects of the macro-economic environment. Both the ESAP and ZIMPREST have had very negative impacts on the Zimbabwean economy as a result of liberalizations, globalization, reduction of budget and fiscal deficits through reductions in social spending in education and health, and devaluation of the national currency. Evidence suggested that women and children were the most susceptible to the effects of drastic reductions in social spending ( Ghosh, 1996 ).

Conclusions

The purpose of the study was not to generalize to the population of entrepreneurs but rather for exploration, model building, and theory development. An objective of the study was to use a phenomenological perspective to elicit a unique image while examining the entrepreneurial careers of women. By using a life-course approach to women's entrepreneurial careers, the role of social constraints in shaping women's capacity and agency for commitment to entrepreneurial careers is recognized ( Carroll & Mosakowski, 1987 ). Such constraints include patriarchal and traditional attitudes toward women and the household responsibilities as wife and mother.